1978. Caprera’s school where you learn to sail

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

Diary at Caprera

Taken from the 1978 Journal of Sailing, Year 4, No. 07, September/October, pp. 38-39 and 62.

Writer Luca Goldoni recounts his experience at the Caprera Sailing Center where he learned the art of sailing. Between unfamiliar names, barracks-like dormitories, and the panic that assails him when he takes the helm.

Luca Goldoni, a special correspondent and columnist for “Corriere della Sera,” is also a sailing man. With his boat, in the summer, he beats the Adriatic routes. We do not know to what extent to learn the art or for professionalism, he was, long ago, in Caprera. Of his experience at the Sailing Center, which is also that of thousands of other young and not-so-young Italians, he drew the motive for a tasty chapter in one of his successful books. He graciously allowed us to publish it, and we do so confident that we are doing a welcome thing for the readers of “Il Giornale della Vela.”

I arrived on Monday with about twenty gentlemen. We introduced ourselves at Linate, much pleasure, but how do you remember twenty last names? After all, in Caprera, surnames are not needed, names are enough. The citizen who on the mainland is M. Rossi, here becomes Mario R. Linate-Olbia with an Alisarda Fokker, Olbia-Palau with a bus, Palau-Caprera with a gozzo, the lantern, the diesel pulsing in the night, standing with lapels raised, an atmosphere of deportees, of Zionists landing illegally. It is an absolute detachment: in Caprera I will not find telephones, I will not find newspapers, I will not find cars. If I have time left, I will only be able to visit Garibaldi: they told me that to learn to sail, seclusion on a remote island like Caprera is indispensable, internship, seminary, convent (or barracks). I have not yet had the courage to ask if I will have a single room or a room to share: this profession also leads to sleeping under trees or in one of the many trenches that continue to be dug here and there around the world, but once the emergency is over, the need for intimacy re-explodes.

I will not have a single, nor will I have to adapt to a double: I will sleep in a dormitory with bunk beds, without sheets, with a military blanket. Thirty years ago soldiers from an anti-aircraft battery slept in this dormitory. Caprera today is a national monument: there are no Moorish-Spanish cottages covering the nearby cliffs of the Costa Smeralda, there is only Garibaldi’s house and the barracks that the navy rented to the Naval League and the Touring Club so that they could restore them and organize the “Civici,” which means Centro Velico Caprera. As soon as we arrived, John, who is the animator of the center, asked for two volunteers for the “command”: they had to go and set the table, they had to wake up in the morning at six o’clock, half an hour before the others, to prepare coffee. When we went to dinner, I found a nicely set table, cardboard plates (which are thrown away: first, the “commanded” was also to wash the dishes), the fork, the spoon. The knife, however, was not there. And I naturally asked what was this novelty, and everyone asked me if I had not read the program. No, I never read the programs, and then everyone else showed me their chrome-plated, stainless knives, full of blades, awls, can openers, bought in London or Marseille, and explained to me that the absence of the knife on the table was an expedient to get them used to using their personal knives.

And then a slight uneasiness, almost a discomfort took hold of me and I said to John if it was necessary all this worship of uncomfortableness, no sheets, no waiters, no knife on the table, wasn’t it a bit like playing boyscouts? Giovanni smiled sweetly and asked me if I had never been on a sailing cruise, and I said no, and then he explained that in the days that followed I would realize that this training in uncomfortableness was no coquetry. Italians, he added, are unfamiliar with the sea, since the time of the maritime republics they have become continentalists, now they are famous as highway builders. For a few years now, in addition to the sea-umbrella, they have discovered the sea-boat, but they buy plastic buoys to take their children for a walk, they buy outboards, or motor yachts to take blondes for a walk. They don’t sail, they get bored at sea. Here on Caprera they learn to sail, they discover what the sea has always been: adventure and risk. I hunted under my deck thinking back to this kind of gospel and was surprised that there was no trumpet to sound the silence.

Tuesday. As soon as I can, I will buy myself a stainless knife: I am forced to borrow it all the time, to open a can, a bottle, to untie a knot, and I feel as uncomfortable as when you have to keep asking: will you give me a light? If one spoke like everyday, perhaps, learning to navigate would be easier but there is terminology, there are dictionaries. Some of the expressions are beautiful, solemn, almost onomatopoeic: “going to the gran lasco” for example, that is, spinning with sails set with the wind in the stern. The models of French boats have delightful names: the lightest, simply, are called vaurien, worth nothing; the boats, larger but nimble, eauvive, living water. Other things I already knew, for example that port and starboard are found only in Salgari ‘s books and that in the navy we say starboard and port. Then I read in the dictionary that one does not say parapet, but broadside; not bucket, but bugle; not hook, but snag; that, instead of artimon, one must say mizzen (and here my bewilderment grows because I do not even know the instead). The instructor, who explains wind on the blackboard, adopts the formula of modern language courses, where from the very first lesson we are addressed in English to students who do not even know how to say good morning.

And in fact he explains that, “to edge, you have to wing it on the hoist without lifting vault from the garrocket.” I have a fit of rebellion and say that I am not here to learn a phraseology that will impress the parties and that it seems quite snobbish to me this exaggeration of code language. He replies that sailors have never been snobbish and that those who sail on the Raphael use the same terms that the men in the brigs shouted: if I go sailing one day and shout to “twist the rope on its hook,” no one will understand me and I may end up on the rocks. He is a pale young man with an engineering degree, his name is Enrico: like all Civic instructors he serves for free. He is cold and mildly sarcastic, often irritating. He doesn’t say so, but he must be convinced (rightly so) that one, angered, learns sooner. This morning four of us went out with an eauvive, I was at the helm: Enrico would occasionally say “orza!” or “puggia!” and I didn’t understand and turned the tiller in the wrong direction. So Enrico probed me: do you think we are upwind or downwind now? And I suddenly found myself in high school, with a pneumatic vacuum.

Later I went out on a vaurien, the wind was gusting, and to balance the boat you had to sit out like on sidecars, I missed a tack, couldn’t repeat it because the rocks were close. Then Henry, from the dock, shouted to throw me into the water and hold the boat. I was holding the vaurien by one side, but the wind swelled the mainsail and the boat was drifting toward the rocks. Henry coldly shouted, “The forestay!” and I desperately tried to remember what the forestay was, and meanwhile the wind was pushing the boat sideways toward the rocks as Henry continued to shout his warning, “The forestay!” And suddenly I remembered that the forestay was the steel cable that goes down from the mast to the bow, and catching the vaurien by the forestay would set against the wind and the sails would deflate. I observed that, in the emergency, memory becomes a caterpillar that digs convulsively and finds. By the same technique I learned which is the “relinga,” and which is the “leech”: the only drawback of this kind of instruction is nightmares in my sleep. This afternoon I was aroused from a brief dream, as a gentleman was patiently explaining to me, “No, this is the zelinda, the zelinda does not exist, at most, she is the cook of a trattoria.”

Wednesday. It is only the third day and it feels like I have been here for a month: the things one does from six in the morning to eleven at night are frighteningly many, the things one learns are unsuspected. One learns, for example, about order this morning I read in the Glenans ‘ famous volume-which is somewhere between a navigation manual and a book of meditations-that “every mistake finds its sanction, not from a higher hierarchy, but from the sea itself; all that is not arranged in order falls, capsizes slips, gets wet, wastes molds.” One learns how responsibility arises from an ongoing struggle of reason against instinct or intuition. One can drive a “formula one” in Monza with instinct and intuition. But piloting this spinning “formula one,” lurching at fifty degrees under a force four wind, there are five of us, and since the rudder has now fallen to me, I am responsible for my four companions, I won’t say their lives, but perhaps their shins and ulnae. And these four mates only do what I decide and I see them from the bottom up, me sunk on the edge that skims the water, them there in the air on the other edge to balance the heel and now we have to do a “gybe,” that is a tack with the wind at the stern and the Glenans ‘ manual says that in the gybe you have to be careful that the “booms,” that is the base of the sail, darting from one edge to the other, don’t mate someone.

And I see the looks of my companions, confident but dignifiedly puzzled, no one can suggest and no one can see that I am sweating cold, because my face is wet from the spray. And I realize what it means to go sailing, it means to be in the same boat more than ever, it means to become very close friends or not to stand each other anymore. It means getting swept up in candid emotion and writing enthusiastic things that, unfortunately, are the opposite of detached, ironic essays. First I satirized cruising on yachts furnished by architects, and now I am here rolling the drum on sailing. The yacht with two thousand horsepower is a caste thing. The sailboat is interclassist, it brings man back to his roots: Giovanni, Franco, Marcello, Ludo, Nanni, what are their last names? Are they chief officers or chief executives? I only know who can lightning counter-bow a jib, I only know what crew I would choose. I can hardly buy myself a sixteen-foot ketch: the important thing is that someone else buys it. Others always need crews, and if I learn how to ply or heave properly, I will go for it.

Thursday. Man overboard, shouted the instructor and threw out a buoy, which, in the drill, was supposed to represent this man who had gone overboard. We were in enough trouble as it was, because we were training to reduce the sails when the wind strengthens and the sea swells: to do these operations with the boat going down under the gusts is to be an acrobat without a net, and one of us muttered aloud that we had had enough of this balancing act already, that it took a sadist to order an emergency supplement to the emergency. The instructor overheard and said something impeccable: it is precisely when you are hooked that the trouble of one who ends up in the water happens. Recovering a castaway when you have an engine is an elementary game, recovering him when the only engine is the wind, with its damned laws of trigonometry, is an adventure, because the wind has no human understanding, it doesn’t turn around, it doesn’t cooperate, it just keeps going on its way. And so we did what they had explained to us in the lecture, we started throwing out everything that floated, jackets, crates, plastic bags, cans: a kind of Little Red Riding Hood path to find our way back after the tack. I, who was at the helm, had to disregard the man overboard, I just had to keep the course to the millimeter; a mate, on the other hand, had to keep his eyes on the castaway-buoy and try not to lose sight of him. After a few minutes, we turned a hundred and eighty degrees: if the course had been exact, going up it, we would find ourselves at the point of the man overboard. It had to be done rather quickly: the sea at Caprera is mild, a clothed man can stand that lukewarm veil of water that forms between clothing and skin even for two hours, but there are “two-minute” seas, after which one recovers a dearly departed. We ascended upwind the path of floating objects until we were at the height of the shipwreck, at which point we had to put on our bellies and let the wind gently push us toward the buoy. I don’t know how I ordered this maneuver, I do know that the instructor told me: bravo, you hit the buoy, however, if it were a man, we would recover a corpse, never seen such a perfect ramming.

Friday. Seasickness lesson. Again, the difference between sailing and motoring must be established. When motoring, everyone bunks up and is sick in peace (the person at the helm is not seasick, just as the driver of a car is the only one who is not nauseous on the roads in tourniquets). In sailing, on the other hand, one has to work and decide all the time, and with an upturned stomach and a cold sweat one cannot work or even decide: there are skippers who, instead of ordering a maneuver, make mild proposals, I would say let’s do it this way, what do you say? And when democracy takes over at sea, it is shipwreck. Seasickness — informs the Glenans’ handbook, i.e., the sailing bible — is not an inconvenience for schoolgirls; there is no sailor with the most proven “sea foot” who, at some point, does not succumb to this crippling malaise. The only solution is to fight it: this morning we were given a dietary lesson, what to eat (legumes, nuts, chocolate) and what to avoid (stews, cabbage, fried foods). At one point I raised my hand and said that when I lived on a fishing boat in the Atlantic for a month, I used to eat an anchovy without bread: if you don’t throw up right away, you don’t throw up anymore. The instructor remarked that I had discovered America and that, if we wanted to stay in the oddities instead, he could give us some recipes: a glass of seawater (suggested by the navigator Slocum), a slice of stale bread (recommended by Breton fishermen) and cherry pit (suggested by anonymous eighteenth-century people). And then it occurred to me to think what ridiculous seafarers we Italians are who, in our little silver boxes, keep so many colorful pills, never having room for a vulgar, prodigious cherry pit.

This morning Nanni, a man from Turin with whom I feel as if we had waged war together, because together we capsized, together we risked being shipwrecked on the rocks, together we were afraid and courageous, asked me what I do “as a bourgeois.” And so we saw how a few days on Caprera sink into distant distances of time and space. The sailboat fascinates because it is an instrument that has remained unchanged over the centuries: even though the hulls and mainsails have been perfected, the laws, the problems, the sensibilities are the same; it clutches or spreads in the wind like the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Romans, like the oldest sailors; the Egyptians, depicted in the famous bas-relief of Deir-el-Bahari, Egypt. It seems to me that for as long as I can remember, my problems have been to retrieve a man overboard, to fight nausea, to spy the moment when the sail spins to tack it right, how to rig a vaurien by securing the mast with shrouds, “inferring” the boom, hoisting the sails with “halyards.” I am reminded of our cars that start by turning a key, one does not have to rig them every time by adjusting the steering wheel, the throttle, the clutch; these cars that, under gusts of wind on the highway, do not heave or punch, at most they lurch a little; that dock at a curb without breathtaking maneuvers. After a week, Franco, who is a Caprera veteran, tells me, you feel like leaving again for Milan, to throw yourself back into the fray that consumes and fuels you; but a week now and then is indispensable, it is total therapy, because relaxation is not the absence of thoughts, which is impossible, but the alternation of different thoughts. There is a little thought, for example. that haunts me: a knot, which is called “gassa d’amante.” I cannot understand it: if it is a test to measure intelligence, it is disheartening. I walk around with a lanyard (or rather with a selvedge, because the lanyard in the sea world does not exist) and practice pathetically. Caprera enters my lungs, it is always swept by the wind, the sky is as clean as if they had washed it with buckets of water. I no longer need a pill to sleep, I hardly smoke anymore. Why don’t the mutuals “spend” a week in Caprera?

Saturday. After seeing them so many days in yellow sweaters or oilskins, my comrades, in their ties and jackets, look as provisional as officers when they put on double-breasted suits. Ours was a crash course, but, from spring, regular fifteen-day ones begin, open to citizens from 17 to 100 years old. You pay little because you are self-sufficient in preparing the mess, serving at the table, sweeping the dormitories, cleaning the toilets. It will be an ideologically disengaged fortnight, but life is also made up of respites, every now and then human experiences are enriching even when one momentarily disengages from ‘civic engagement. On Caprera, young gentlemen and workers gather, some leave after two days, those who remain are infected by this ancient, almost biblical way of going to sea. One also learns, among the laws of physics and human laws, singular habits of propriety: for example, that the British at sea, after the change of a crew shift, wait at least half an hour to change even slightly the setting of the sails, so that this does not seem rude to the dismasting “guard.” Except for the “a gassa d’amante” knot, I also understood many things: I understood and discovered the sea, which I also had sailed so many times with an ocean liner, a moscone or an outboard. I leave my companions at the Fiumicino airport. we greet each other, we exchange addresses, we especially exchange last names: we had survived seven days egregiously by ignoring our family trees.

By Luca Goldoni. From “The Fish in Midwater,” Arnoldo Mondadori Editore.

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

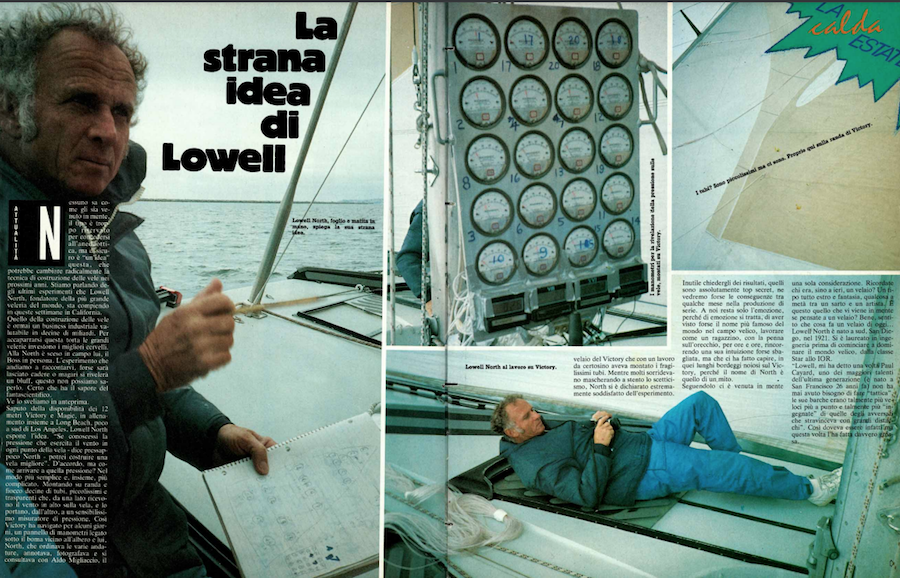

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions