1994. When the sailing revolution was born

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

When the sailing revolution was born

Excerpted from the 1994 Journal of Sailing, Year 20, No. 10, November pp 56/65.

It is called Wallygator II, is 105 feet long, reaches 30 knots of speed, and is all controlled by sensors and hydraulics. The Journal of Sailing notices that with the Wally 105 a boat was born that would revolutionize the history of yachting. And he reveals the secrets of this revolutionary object.

105 feet in length, 60,000 kg in weight, 30 knots in speed, 700 meters of hydraulic hoses, more than 200 sensors. These are the mind-blowing numbers of the new Wallygator II, the revolutionary cruising maxi.

While smaller sailboats, so to speak, those up to 50-60 feet in length, experience a slow but steady evolutionary process involving both shapes and materials, the world of maxi cruising yachts appears plastered within strictly traditional canons. Every now and then, a few more imaginative designers attempt a renovating move, slimming down a section, modifying the soaring a bit, removing a few too many tons. But the trend remains more or less the same, heavy displacement tugs “penthouse-super penthouse-terrace” style, mammoth structures forced to undergo stresses that force the need to oversize everything from the framework to the rigging. Ultimately, on these boats the trade-off between performance and comfort leans decidedly toward the second of the aspects. Wanting to find a justification, it could be argued that studying new shapes and solutions for large sailing hulls involves extremely expensive research work, heavy to bear even with the budgets of a maxi yacht. Especially if it lacks a structure to which all information converges, capable therefore of making material technology interact with fluid dynamics, hydraulics with electronics, design with seamanship. And that is what Luca Bassani has set out to do with Wally Yachts, a team of professionals who study and realize the boat as a whole, from the identification of the owner’s needs to the execution of the project, up to the choice of the shipyard and suppliers, so as to relieve the client of any possible risk associated with having to deal with multiple interlocutors, while seeking the best value for money. All with innovative criteria involving the use of the most advanced technologies, without which a light displacement boat would have no reason to exist. Bassani, who in addition to boasting a great deal of sailing experience (he was one of the “historical” owners of the IOR, as well as a two-time European 6-meter SI), knows the yachting industry well, having been the owner of Barbarossa and Harken, already in 1989 showed that in the maxi cruising segment, there was still a lot to be said again. Wallygator, an 85 “built by Sangermani to a design by Luca Brenta, summed up what would later be the philosophy of Wally Yachts, ‘fast & easy sailing’:light displacement for high performance, but with large spaces above and below deck and above all maximum simplicity in handling. That boat served as the first test bed, followed closely by Boabunda, a 60” IMS cruiser racer, and Rrose Selavy, a 65 “IMS. In the meantime, the idea of Wallygator II was born, a 105” maxi yacht that would revolutionize the old way of big cruiser sailing, a second testbed where new technological solutions could be tested to create the know-how necessary for Wally’s future. You can see the result by flipping through these pages, although to x-ray and understand Wally 105 would not take the whole magazine. In fact, it is not its line and appearance that make it such an original object, so much as the engineering behind every smallest detail of this boat of over thirty meters.

Design and construction

Making a 105-foot light displacement yacht involves quite a bit of research work. First, the problem of pitch on the wave, which risks being too “nervous” must be solved: that of interior volumes, which the absence of hull dive tends to penalize: and then the most obvious, but perhaps the most difficult to deal with, which is keeping weights within much stricter values than for a heavy displacement, because an unplanned ton risks varying barycenters and symmetries. After months of tank testing and computer simulations, where various hull configurations were run over by wave trains to test their behavior, designer Luca Brenta found the solution in widening the sections from the maximum beam towards the stern and thinning those at the bow, while maintaining a ‘high longitudinal inertia given by an extremely developed waterline. The high stability of form is matched by a ballast-to-displacement ratio of 40 percent, with a center of gravity well below the waterline. Large sections naturally mean large interior and deck spaces, which on Wally are comparable to those of a boat at least twenty feet longer. That leaves the third point, which is weight maintenance. This is where composite materials come in, which have saved 50 percent of the weight of a more traditional construction. The hull alone comes in at just 12.5 tons, and is made of a super-tech sandwich made of differentiated PVC cores (ranging from 80 up to 130 kg/sqm), with an outer skin of glass-kevlar hybrid quadriaxials, which provide the necessary impact resistance, while the inner skin is made of carbon fabric, for maximum stiffness. The laminate is made with epoxy resins, vacuum and post cure. The deck core is honeycomb, as are the bulkheads. The furniture is structural. Displacement is 60 tons.

Plumbing

It is the heart of Wallygator, consisting of four pumps and seven hundred meters of “arteries” that distribute energy (something like 500 liters of oil per minute) to the various utilities. Let us briefly describe the operation of this absolutely innovative plant. It all starts with two Yanmar diesel engines of 175 horsepower each that, instead of the common inverter and shaft line, have a gear coupler. Each of these couplers runs two variable-flow hydraulic pumps, which send oil to a series of exchange valves. This directs power to the watermakers, the generator, the propulsion systems, and a multitude of services such as opening the stern hatch, raising and lowering the centreboard, winches, mizzen sheet, windlass, etc. Even the hatches are hydraulically opening, you press a button and the hatch (custom carbon of course!) closes. What’s special about this system is that you can use the utilities at the same time, feeding them each with different pressures but with a constant bar input, with no drop in power. Usually, in a hydraulic system, the pressure enters, let us assume, at 150 bar and exits at 150 bar; if I have to feed more utilities, I have to increase the oil supply, otherwise when I press a button on the halyard winch while I’m hauling the anchor, the power on both drops: in this case, however, 150 bar enters and 150 bar exits on one utility and 200 bar on another. Adjustments can be made either by increasing the speed of the diesel engines or by varying the pump flow rate. Of course, there is a manual safety system that replaces the diesel engine should it fail (a rare occurrence, however, since there are two of them, and each engine alone is capable of powering all the hydraulic pumps). Needless to say, the study required to create this system, the work of Gianni Cariboni, was immense.

Propulsion

Another of the wonders of Wallygator is the propulsion system. In fact, the “hydraulic” heart, which we described above, transmits the energy needed to move two propellers, without inverters and shaft line. In their place are two thrusters, that is, two retractable, 360-degree pivoting feet, which propel Wallygator to a cruising speed of more than 12 knots. One thruster is placed at the bow, like a common maneuvering propeller, the other is placed at the stern. By sailing they re-enter the hull decreasing friction, with a gain of about two knots. In addition, no longer having to optimize the propeller shape for sailing, the most efficient conformation possible could be installed: four-bladed propellers that instead of pushing, pull. So in forward gear, the foot faces forward and not aft, so as to take advantage of less turbulent incoming water and improve thrust. The stern propeller measures just 600 mm in diameter, the bow one 500 mm, with two engines of only 175 hp, light and compact, moreover extremely fuel-efficient compared to the power that would be needed to move a yacht of this size. When the decision is made to go motoring, one button is used to control the descent of the thrusters (or even just one of the two), and two joy-sticks are used to direct the thrust of each propeller forward or backward, but also at 45°, 90°, 135°, either to port or starboard. This means being able to carry out any kind of maneuver. for example, getting out of a dock that you are moored to with the wind pushing perpendicularly, by simply flexing the two joy-sticks in the 90° position toward the open sea: the boat magically moves sideways. But the main advantage of the hydraulic transmission is that you are totally free in positioning the engine. No longer having to submit to the conventional shaft line, you can install it where it is most convenient. Only two one-and-a-half-inch diameter tubes run the propeller anyway. The two thrusters are also the work of Cariboni, while the propellers were designed and manufactured by Hydromarine.

Wallygator II : Masts, sails and deck

As is well known, light displacement yachts benefit from an extremely favorable “power-to-weight” ratio, which enables them to develop exciting speeds, especially at wide gaits, with very small sail areas. When, however, this yacht is a 32-meter cruiser racer that opens something like 530 square meters of canvas to the wind (upwind!), the solution to manage maneuvering with only four crew, without resorting to furling systems, becomes more complex. For this, Wally Yachts relied on a specialist like Chris Mitchell, who created a ketch sail plan, which in cruising has a fully battened main and mizzen and a self-tacking jib at 95 percent of the J, inferred to the forestay by means of traditional garrots. The distribution of surfaces, reminiscent in some ways of that of the latest maxi Whitbreads, is thus very balanced without, however, chastising the aspect ratio (the mainmast measures m 38.5 from the deck, the mizzen mast m 28.4) so as to provide high potential in light winds, but at the same time allow sailing up to 35 knots of apparent without changing sails, limiting reductions to mainsails only, which are known to be easier to control than headsails. Halyards and sheets are, of course, handled by hydraulic winches. With this rigging, Wallygator tackes without needing to touch a sheet; the total absence of flywheels and staysail, allows the wind to be upwind simply by turning the wheel. Of course, without the use of high-tech materials, this would not be possible. And in fact, Wally’s carbon masts, made by the American company Omohundro, resulted in a 50 percent weight saving (over two tons), which translates into greater stability and consequent sail holding. The highly angled shape of the spreaders and a quarter as wide as the boat (the heaths are placed in the hawser) provides the necessary longitudinal stability.

Wallygator II Deck plan

What is striking about Wally is the absolute cleanliness of the deck and the ergonomics of every passageway. All rigging is recessed partly under the gunwale and partly under a central mock deck. The cockpit has a retractable dodger that uses the mainsail sheet rollar as the main truss and creates a huge sheltered area. All fitting was designed by Harken.

Tender

The tender is housed in an authentic aft garage. Studied by Victory Design, the tender is an architectural marvel: it is in fact equipped with a diesel engine, so it uses the same fuel as the engines, and Arneson-type surface propellers.

Anchoring

One only has to look at the bow to see that the anchorage is also nontraditional: no nose, no chain passages. The anchor comes out of a watertight housing at waterline level, four meters abaft the bow, with obvious advantages in terms of pitching. Also solved are the problems related to pulling the anchor, which always involves a very elongated snout.

Wallygator II Electronics

On boats of this size, keeping onboard management under control is one of the most delicate and challenging tasks. The systems are many and complex, and an oversight can cause even very serious damage. Engineers from Servowatch, a company specializing in computer programs, have specially created an electronic control system for all major equipment and more that allows the boat’s “life” to be kept at bay by simply pushing buttons on watertight “touchscreen” monitors placed at strategic points such as the wheelhouse or charting. Basically, menus appear on these screens, displaying a range of information in real time. Which ones? For example I want to know the water consumption, I press the relevant file and the amount of water in the tanks and its daily consumption appear. So for diesel fuel, electricity, exhaust gas temperatures, etc. Of course, each indication is accompanied by visual and audible alarms, warning of entering reserve or of a problem on the system. In addition to this information, Wally’s “Servo” provides rigging workloads, the situation of the hydraulic circuit, controls the opening of valves, the position of thruster hatches or anchor. A total of 380 pieces of information, corresponding to as many sensors scattered around the boat. Including two sonars placed in the bulb torpedo that signal the presence of a submerged obstacle up to 200 meters from the bow. Sailing at 10 knots, that’s about forty seconds to avoid an obstacle. Meteosat, Saturn C, Radar are just some of the equipment on board.

The interior of the Wallygator II

Although it is a light displacement, Wallygator has surprising interior volume due to the considerable width of the sections. Just take a look at the salon, forty square meters of area divided into dining area, where an almost three-meter table stands out, and reading area, to realize that it is first and foremost a cruiser. But what one also appreciates is the sobriety of the lines, without any details that clash in the least with the spirit of essential seamanship proper to a real sailboat. In the distribution of rooms, two notable details should be noted: first, the division of owner’s guests in the bow and crew quarters in the stern. This is nothing new; by now many designers and owners have understood the advantages of this solution: sleeping away from the facilities, cockpit and dock noise. On Wallygator, however, the problem of sailing forward in rough seas, when the forward cabin becomes uncomfortable, has also been solved by making a fourth guest cabin, located on the opposite side of the charting, right amidships. The other remarkable aspect is that the interior is designed as a living quarters intended for long and demanding sailing. Any examples? There are no double berths, but rather comfortably sized single berths with anti-roll bars. The crew area includes a separate pantry equipped with cold rooms capable of storing oceanic galleys, a laundry room and waxed area. All in all, an excellent combination of comfort and, why not luxury, without ever forgetting functionality.

Leonardo Zuccaro

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

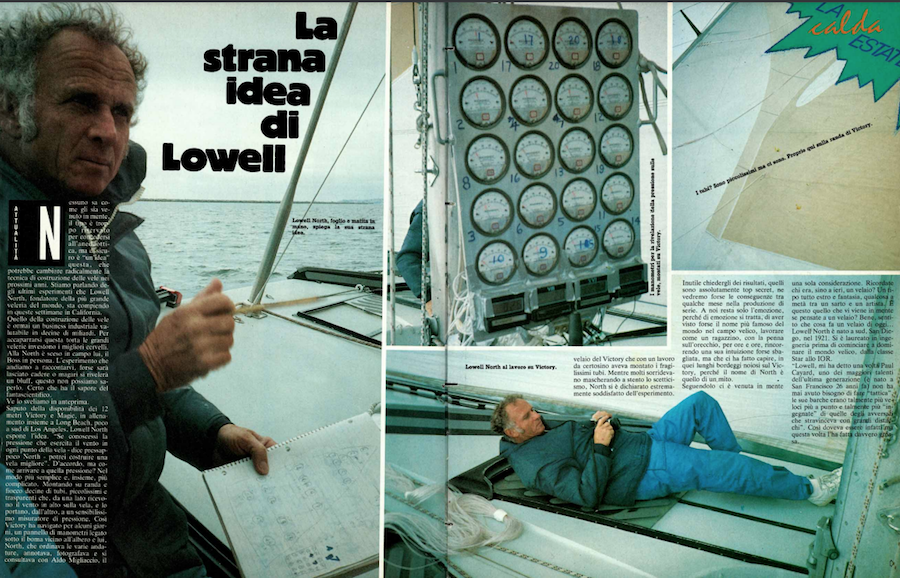

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions