1994: Oceanic thrills for four Italians

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

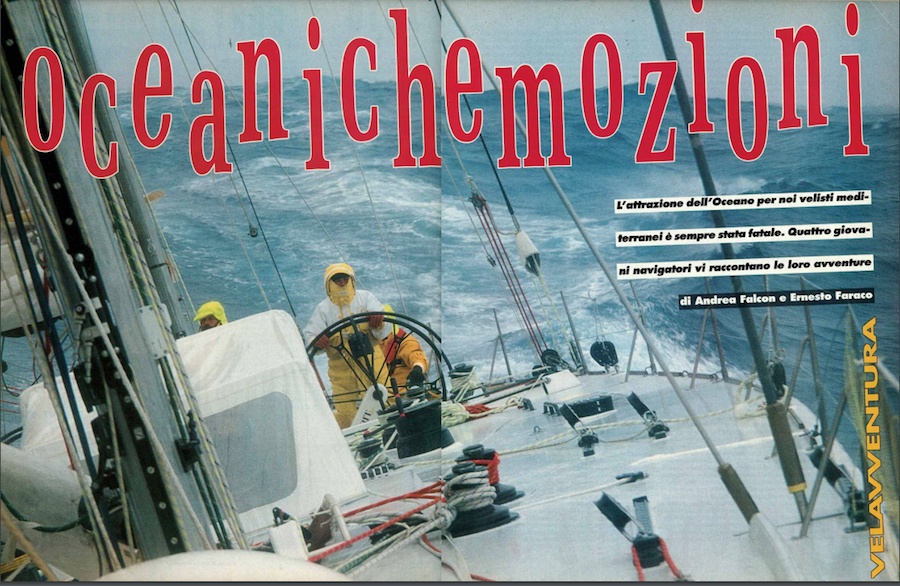

Oceanic emotions

Taken from the 1994 Journal of Sailing, Year 20, No. 1, February, pp. 34/39.

The 1990s tale of four young Mediterranean sailors recounting their ocean adventures. Like 30-year-old Peter D’Ali who says, “At the 52nd parallel everything seems impossible to you.” Or Marco Zancopè who aboard his 6-meter Mini when he crosses the finish line bursts into a liberating cry.

Leaving for a sailing regatta that has for its course a round-the-world or ocean crossing, represents for some a simple work commitment, a sporting adventure, for others a kind of Puerto Escondido, an escape from the routine of everyday life. In the end, however, both the coldest of professionals and the most emotional of fugitives cannot remain indifferent to impossible scenarios and situations. Both find themselves experiencing unique emotions and sensations, emotions capable of being experienced only by those who have sailed in certain winds, with certain waves, at certain temperatures or at certain latitudes. Many of us have as our dream a participation in a round-the-world race or an ocean crossing, but it is wrong for those who underestimate the laws of the oceans to the point of believing that the Atlantic has now become a pool in which we swim easily. For the time being, while waiting for the chance to tell your oceanic story, settle for the tales of experiences directly from some of our friends, recent veterans of adventures and misadventures while sailing among our Earth’s most respected oceans.

Rodolfo Guerrini: I will never forget that sky

Rodolfo Guerrini, Rudy to everyone, a past dental technician now bowman on Merit Cup, the Swiss ketch-rigged maxi competing during this still-ongoing edition of the Whitbread around-the-world race, earned his place after a long and tough selection process managed by the boat’s skipper himself, Pierre Fehlmann. Guerrini, 32, from Rome, along with Giovanni Ferreri from Turin, Italy, is one of two Italians embarked on Merit Cup. The first Italians in Whitbread history to win a leg. “When you leave for a leg like this you are aware that you will find adverse weather conditions, however at sea, even when you do a short race, you always find the unexpected, and so the sea must be taken with a certain respect. With these boats we are prepared to race to the maximum, whatever the wind and sea conditions are. The crews are aware of what they are doing. The risks are there, but ours is not a crew of fools. The first thought is the regatta, there is a desire to do well, the goal is to compete. You have to remember that in this regatta even if you don’t see the opponent, you know his position always, how many miles he gains, how many miles he loses, and that spurs you to go faster or pull even when there is a lot of wind. You have to be careful to manage the sails well, the crew, so you don’t split. Sometimes it pays to anticipate a maneuver so that you don’t get into such difficulties that could then cost you a sail, your equipment, the race. Compared to the Mediterranean, in the South, at these latitudes, there is always wind. We are used to the gust of wind but predominantly there is becalmed. Here, on the other hand, the wind is always constant, around 20, 30 knots. Something unthinkable for us. What will forever stick in my memory? The sky of unreal brightness, the majestic and powerful waves, and the everlasting company of these black birds, the albatrosses, the birds of the South. But the greatest thrill was the sighting of my first iceberg. It was an ‘island of ice with the top shrouded in clouds, it looked like something mystical. A surreal sight. Every degree you go further south you realize the difference in climate and natural scenery. Every degree everything changes: from the color of the sky, which first is clear with clouds, then as you descend it gets darker and darker. Below 50° south latitude, on the other hand, the sky is always like muffled, a cold wadding that doesn’t allow you much visibility. Sometimes there’s fog, but it’s not our fog. it’s windy and it’s something that limits your visibility, a real cold cape. It’s like being in a refrigerator. The only hours of sunshine are those that accompany the passage of a cold front, then the wadding comes back, visibility drops, and you’re back in solitude. This happens because the boats are very fast, averaging 16 knots, so you drop in latitude very quickly. We also started this leg upwind, immediately with thirty knots on the nose. Then entering the roaring forty we sailed with thirty, forty knots all the time. In these conditions the mizzen most of the time is tied to the boom; in fact you can’t bring the boat with the sails behind, otherwise you’ll oversteer every time you set off on a glide. When this happens it is still preferable to be on deck to realize what is going on. Inside you just see everything flying without knowing why.”

“It is cold. The water is at one degree temperature. One day during my first quarter of an hour at the helm I was without gloves, when I tried to put them on it was too late, my hands had swollen too much, the gloves didn’t fit anymore. When you sail you always have a dozen birds following in your wake. How strange that here, at the edge of the world and in this horrible weather, these flying acrobats always follow us. Minus three. This is the record temperature of the stage. The night is hard and cold, the deck freezes at times as well as the windex and halyards and everything else. When I have to go on the tangon for a peel I have to take off my gloves and when I’m done, and I go down on deck, I’m not able to move my fingers, so it pulls another one in. I mean in Campiglio at least we would go to Bepi’s and have a grappino, not here. Once to retrieve a sail that no longer wanted to slip on the forestay, we were forced to heave abruptly to get the relinga torn. Imagine the madhouse of recovery. In these latitudes I serfed the biggest waves of my life. After we passed the Kerguhelen Islands things started to get better: in two days we gained more than 16 miles on NZ, went down with more than 40 knots while maintaining very high averages, peaking at up to 26. Not bad. The waves grew bigger and bigger, in height and length, since the passage of the islands we have exploded three gennakers, just a little, an ill-judged rump or a little nettle of the helmsman or a crossed wave. John did nothing but sew sails: never be a sailmaker on these boats! Snow and hail often come with the rigging, think of the beauty. Record overflow: one morning we lay on the water at ninety degrees. I admired Bruce Farr‘s work. Perfect keel and wonderful rudder! I got to watch them carefully as I clung to the deck waiting for the boat to right itself. Memories overlapped. And my first experience of the Big South. Pierre, who is our fifth time in these parts, tells us that the Big South has graced us: few storms, few ices, few difficulties. That may be, but I wasn’t there the other times, and now, in spite of the difficulties, I’m sure I’ll be back to poke around down here.”

Pietro D’Alì, sailing at all costs

Pietro D’Alì, 30, from Milan, is on his first experience in ocean sailing. On dinghies he is one of the top talents on the Italian sailing scene. This year with Star, the queen and most technical of the Olympic classes, he won the Spring European Championship and the Italian Championship. His great knowledge of sail tuning and this having sailing in his blood has earned him a place as helmsman of the only Italian boat entered in this Whitbread. For Pietro this is a new life experience in a year of transition, looking forward to returning to racing on the Star when the federal programs are clearer. Pietro is a “sail at all costs” kind of guy. He recounts, “On December 3 there were 35 knots of wind, we were about to take off the smaller asymmetrical and I had just finished the turn when I heard a crash. I rushed to the stern, on the rudder, because the crash was coming from there. I saw a tide of water coming into the boat: It was not good. When you’re sailing at 52° south latitude and you see water coming in on board, for a moment you think all is lost. The first impact is one of shock. You see this water coming in and you think, it’s not possible, it’s not possible! Then you react, you don’t give up and you do everything to keep the boat afloat, even though the first moments it seems an ‘impossible feat. After a few seconds of amazement we all rushed with buckets to remove the water. Our problem was that the rudder was stuck under the hull and would not go away. The sector was in danger of widening the hole created by the broken shaft, and causing us more damage than we had, to the point where it was irreparable. We had to saw off the sector to free the rudder, and it was a very long operation because we had to work in the very cold water, which was up to our waist, which had filled the whole aft part where the maximum height is less than five feet. In short, we worked as divers in the freezing 2-degree water. It was a really difficult operation. In the end we managed to get rid of the rudder by jibing 6 successive times while from inside with the hammer we were pounding like crazy. Fortunately in those moments you stop thinking, you just go at it as hard as you can and that’s it. I think it was inevitable then, for our skipper to activate the distress signal, the EPIRB. The radio was now out, so even if we managed, as we did, to keep the boat afloat, it would have been a problem to stay for many days without giving our news. We would have kept everyone in anguish for 10 days. And then with the water at those temperatures you think if you’re going to go on the raft you’d better have someone warned and come looking for you right away, as soon as possible. Of course the Jury should set strict rules about the location of communication tools: without rules it’s obvious that everyone tends to put the radio repeater, really heavy stuff, as low as possible, within reach of the water. Emergency signals should also be differentiated: only on land did we discover the value of an EPIRB signal. Finally, everyone should have an emergency rudder to hang from the stern as we did. Having freed the boat from the rudder five hours later, we found ourselves with a 35-centimeter hole to plug. Here we were really good: we closed the hole perfectly. The bottom of a bucket, held under pressure with the tangon bouncer and tinned with mats and silicone was our solution. So we started to empty the boat from the water. By 10 p.m., more than 14 hours after the start of this misadventure, the situation was perfectly under our control, and we raised the tormentor and set course for Fremantle again. Two hours later we spotted the lights of La Poste. They had found us. Via VHF we made contact confirming that we were able to continue by our own means.”

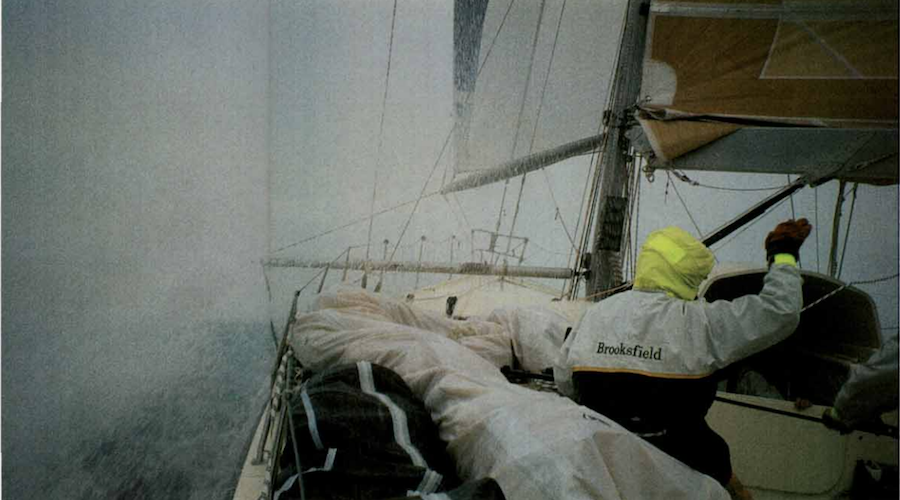

“Through La Poste radio, Guido Maisto was able to communicate to Italy and England that we were all safe and sound. We told La Poste that he could continue but the arrival of a bad depression convinced Daniel Mallé to stay close to us. During the night the wind at over 60 knots forced us to put us in the hood. I thought we might be in the little boat in those conditions as well. Instead we were all on board and Brooksfield sailed safely. This experience confirmed to me that I enjoy sailing, I am the only one on board who has gained weight instead of losing weight. In these situations there are people with whom one is better off and maybe it increases and consolidates a friendship there are then other people with whom one was already uncomfortable before and so one tries to avoid confrontations. We are professionals. It’s not a cruise so you pick and choose people. It is certain that in those moments everyone reacts as they are, you cannot cheat. Stefano, who is generous, froze his feet to keep the leak at bay for over 4 hours, others called out. To do this regatta you need a lot of passion for the sea, because a month in the boat in these conditions if one does not have a lot of passion is unbearable (flooded cockpit, always wet and fast, ed.), endurance to cold and fatigue, so you also need good athletic preparation. Therefore, if one is impatient and cocky, it is better to stay home. It should be added that W60s are big drifters: one travels on the narrow reach with the gennaker at unimaginable speeds. The log never drops below 18 and swings up to 23/24 knots, like a catamaran. This is very tiring because the waves pass over the deck, the spray reaches the helmsman, the center cockpit is always flooded, you have to keep the sheets in hand because you risk a strake at any time, you have to follow the waves a lot with the rudder just like a dinghy the boat is always in constant glide. Great thrills then, but in these latitudes it is always too cold and when you don’t have a heater to warm at least your clothes, one always stays wet, even when going to sleep. So the oilskins and clothes you have to carry them in your sleeping bag, warm them with your body and wear them, or keep them on all the time. Sometimes you happen to wonder but who made me do it? But then when you get ashore you always dream of starting again. It’s a spring that one has inside, maybe it’s the fact of going against the unknown, against the unexpected, that drives you to these feats.”

Marco Zancopè: brave and unlucky

Marco Zancopé, 28, an architect, now lives in Guidel, France. He participated in the last edition of the Mini Transat, the transatlantic race for solo sailors with boats no longer than six and a half meters that is held every two years. Broken rudders denied him a historic victory, in a very particular sailing world monopolized by the French and which only in recent years is also involving Italian sailors. Zancopé decided to participate in a solo ocean race because he believes this type of sailing is capable of marking a sailor’s life differently from others, more deeply. He says, “After the cannon shot that kicks off the race, we are all still: a minute’s silence so as not to forget Pascal(Pascal Leys, who went missing during the storm at the first start of the Mini Transat: his boat was found overturned and the rescue boat empty, Inside me, however, there is no silence. To him I have thought in due time, and the deep esteem I have for Pascal certainly does not make me forget him. I unwind the genoa and Tea Salt sets off toward the short stick course before setting the broken 200-degree bow on Palma, where I mentally set my first flying finish line. It charges me much more to know that I have to concentrate hard, to bring my boat to its best for only two hundred and fifty miles instead of the two thousand nine hundred of the entire course. I am afraid that this would lead me to think I could lift my foot off the accelerator and rest, so long is still a long way to go! Light winds in Funchal Bay and barometer at 1019 mb. Everything as planned. After lowering the big spi I am on course for the disengagement buoy. Thierry Dubois (who will later win the Mini Transit on Amnesty International, ed.) is a hundred and fifty meters ahead of me. First night falls, the lights of Funchal recede, I change genoa to solent, then again to genoa. I keep to the west of the direct course, then have a chance to gybe and enter narrow left sea as the wind turns and strengthens from the north near the Canary Islands. Almost all the fleet is on my downwind beam, only Thierry has chosen to sail west like me. I am calm. in my head there is a Transgascogne rather than the Mini Transat. I am convinced that in order to win one must not get lagged in the first part. Besides, all the regattas done during the season with Tè Salt and all the transfers, make me feel comfortable, sitting in the cockpit with the stick now in one hand and the sheet in the other. The pressure of the days leading up to the departure from Funchal is fading, La Transat you have to attack it exactly like the races I know well: once at sea, there is no difference with a triangle race in 470. What changes is the preparation before the race. It’s starting to get light, I don’t see any other minis around me. The wind has let up a bit and turned northwest. The gennaker pulls me out of trouble at five knots. I keep telling myself ‘push, push, stretch on the others.’ Inside me, in my brain, I have like the nautical chart with all the positions of the most dangerous opponents.”

“I feel that I am gaining. The passage ofPalma Island is not the easiest. Without GPS positioning we chart with the ‘help of the radiogoniometer and sextant estimation. I want to pass away from the coast of the island to avoid running out of wind. I say to myself, ’round it well, it’s not an inflatable buoy. If you go even farther, with the northeast stable at thirty knots, you’ll catch up right away.’ I freak out at seven in the morning to put my starboard tack in the middle of the channel between Gomera, Tenerife and Palma. I’m now sailing a 270-degree course, the West Indies in my face. I call Thierry on the VHF, we talk well on four watts, we are very close. He asks me if I am afraid when I think of two thousand five hundred miles of crossing ahead. I tell him no, everything is fine on board, I’m just a little wet. The excitement of burning up the ocean at ten knots of speed and passing the first buoy first is really great. I come out of the channel between the islands with the genoa bompressed and one hand to the mainsail. I laugh like an idiot thinking that this is all the work of three years. I am living the best dream of my life. It has cost me at times very dearly, hours of cursing and swearing against the sea and the wind, against the jinx, against me. The cold, the wind, the fear of a sea never seen before in Biscay. The anguish of the fog, all the times I said to myself, ‘but who made me do it.’ I attach the pilot and go down to get something to eat and do some sailing. The wind, as I move away from the islands, turns east. I lower the genoa and hoist the small spi. I am afraid I have waited a little too long to make this decision. I know Thierry is not one for gifts. With him every left is lost. Bruno Le Grand on Dephermerides and Yves Le Massonon Port de Trebourdain, they are quite detached, I cannot hear them even at twenty-five watts. I sail all afternoon at speeds between twelve and sixteen knots. A spectacle. Way to go Zanco, don’t let them detach you, every mile lost today is ten to make up tomorrow. At night I see a freighter, ask its position, then get some sleep, check that everything is okay. At eight o’clock in the morning on November 8, the dream is shattered. I start the generator to charge the batteries, pass on battery 1, a power jump, the pilot stops and Té salt jibes, nothing tragic. I get out to put everything back in order and see the starboard rudder in the waves. A punch in the stomach. I go to the bow and immediately lower everything, stop the boat. The other rudder is also on the verge of leaving, the stainless steel cheek welds have already quit. One screw, the foremost one is headless. I replace it, screw it in as much as I can, but as soon as the operation is over I collapse on my knees crying. The regatta, for me, is over. A year and a half of work passes me by, all the times I checked those parts. The doubts. the perplexities, then the certainties, the modifications. I call by VHF one of the support boats, bring her up to speed, and ask if she can give me extra food and water, because I have the impression that the crossing could take up to thirty days. With a makeshift, makeshift rudder, one cannot make more than five knots. From here until the arrival in St. Martin, the story is more like that of the Kontiki than that of an ocean racing boat.”

Andrea Romanelli: living a dream!

Andrea Romanelli, 30, of Udine, has a degree in nautical engineering and works at Cantieri Tencara. In 1979, at the age of 15, he flipped through the December issue of the Giornale della Vela and found a feature dedicated to American Express, a revolutionary boat that had just won the Mini Transat. Andrea fell in love with that boat, which he then managed to buy in Christmas 1992 in England. He decided to cross the ocean solo at the last edition of the race, driven by his great love for the sea. He is also fascinated by other types of ocean sailing, such as even the Whitbread, but in solo sailing he is better able to combine his passion for the sea with his passion for racing. A curious fact: among the Italian boats that have sailed outside the Strait of Gibraltar this year, devoting themselves to ocean crossings, tours of England or the world, the Secifarma of Romanelli is the only boat not to have broken any rudders. Secifarma, the former American Express from 1979 precisely, is a wooden boat. The seventh place won at the end of the regatta represents for Andrea Romanelli only the classic icing on the cake. His emotions were quite different. He recounts, “After endless months of preparation, we are finally off. I am living the dream. The waves rock the boat and shock me to the deepest core. I am mesmerized by the power and energy of the sea that seems inexhaustible. The boat feels like a horse gone mad. Upwind with forty knots I leap off the waves imposing unheard-of accelerations on the whole boat and myself. I realize that under gust, at fifty-five knots, I am sailing at the limits of endurance for the equipment and that a small breakdown could be fatal. A little recklessness and the grandeur of the natural spectacle make me feel good; I am happy to be alone on my boat in the middle of an extraordinary sea. The leg is cancelled: after a few days ashore, it is the worst moment of my adventure: Pascal Leys‘ boat and raft have been found. It is a bad blow that makes me reflect once again on the meaning of it all; I am reminded of the many difficult moments and the sacrifices made to succeed in this endeavor. In the end the scales tip on the side of ‘sticking it out,’ for me the game is worth the candle. In the Canary Islands, I find myself in low spirits due to a major navigational error that forces me to come back upwind fifteen miles as others press on under spi rounding the island far ahead of me. Morale is not cero helped by some absurd risks I allow myself to take to try to catch up. I feel I am getting too caught up in the rankings and it is all to the detriment of safety and boat speed. I’m taking a night of reflection and the next day dawn triggers.”

“I begin to be relaxed, at peace with myself and everything around me, the waves seem to roll from infinity at the stern to infinity at the bow, to hell with ranking, I have to squeeze the boat to the maximum, enjoy the crossing and eventually it will show. The exhilaration is increasing every day and the sea is great. I have the feeling that I am behind in the rankings and I am determined not to give up a single meter to the opponents. The glides follow one another interminably and under spi I continue to improve the boat’s speed record, I come close to two hundred miles in the twenty-four hours. Runaway, one of the assistance boats, in one of the few VHF contacts I manage to make, informs me that the Zanco(Marco Zancopé on Té Salt, ed.) has problems with his rudders and that, having asked for assistance, he is out of the race. I am enraged. Our friendship was born three years ago talking about this adventure, which with great enthusiasm we are living together in the same edition. The end of his dream leaves a bitter taste in my mouth. I feel a bit like the last bastion of an ‘Italian expedition’ that to this day I believe deserved more. It is very difficult to dose the gas, any stupid thing could put an end to this fantastic dream. I spend about sixteen hours a day at the tiller to minimize risks and to lose as little road as possible. For entire days I feel like I am aboard my contender, the glide is practically continuous, and spikes in speed above fifteen knots are now a daily occurrence. As I descend south I alternate between moments of enthusiasm for the performance of Secifarma to moments of complete rapture from natural spectacle. The sunrises and sunsets are overwhelming with their play of color. The seabirds, with their flight almost touching the waves, keep me company throughout the crossing. I feel full of energy, so much so that I overcome difficult moments such as breaking the boom and mainsail with surprising speed. The sailing goes on between squalls, gusts, small breakdowns and the eternal fear of breakage. The last few miles are upwind, two hands of reefing and the Olympic, I am on my way, I make the last tack, about half a mile to go, the bow points safely over the finish line buoy. My thoughts turn once more to Fabrizia with her burden of affection, to my brother and my friends who helped me. I hear the finish siren. Me and my boat made it. Unbelievable, besides seventh place I am in seventh heaven!”

by Andrea Falcon and Ernesto Farace

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

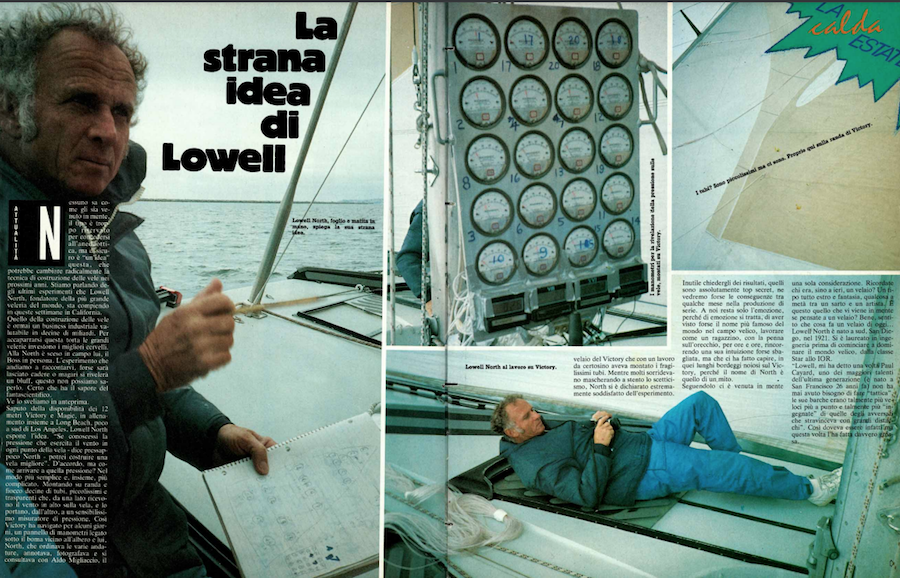

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions