2008. Joyon, that’s how you become a holy monster of sailing

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

Joyon, that’s how you become a holy monster of sailing

Taken from the 2008 Journal of Sailing, Year 34, No. 02, March, pp. 60-68 .

At 51 years old, solo French sailor Francois Joyon pulverizes the round-the-world record in 51 days at an average speed of more than 19 knots. We tell you the story of one of the holy monsters of world sailing, massive as a rough stone with eyes shaped like seaweed.

The tale of the world tour record and its hero

He is the least handsome sailor on the globe, the man who pulverized the record for sailing around the world solo, in just over 57 days, at the fantastic average of over 19 knots per hour. Francis Joyon is as massive as a rough stone, his eyes are shaped like seaweed, and he is not even a kid, he is 51 years old.

To get him to say a word you have to corkscrew it out of him, he flees journalists like the plague, “they give me anxiety,” he says. Yet Francis Joyon since Jan. 21, when he crossed the finish line in Brest, Brittany, has been the myth, the hero of all sailors around the world, the man who shattered, improving it by 14 days, the record set by Ellen MacArthur in 2005. This living legend was born on the great agricultural plain of the small and remote French region of Eure et Loir. As a teenager he experienced sea adventures by proxy, devouring the books of Moitessier (great French hippy sailor of the 1960s, ed.). He discovers the sea, at 17, by riding his bike to Concarneau, Brittany, where the world’s most famous sailing school, the Glenans, is based. He finally goes to sea, learns how to tie knots and build a hull. He is already 32 years old when he begins to deal seriously with boats. And he happens upon Elf Aquitaine, the former Marc Pajot catamaran, which is a real scrap. But Joyon doesn’t lose heart; mindful of his previous trade as a carpenter, he salvages the transoms of another tri, the Roget Gallet, and hoists the sails of Biotherm. It seems incredible, but his first boat stays afloat. He will sail it for eight years, no wins, many breakages. The sponsor, challenged gives him the 60-foot trimaran with which in 2000 he won the British Transat (formerly Ostar), even setting a record. Always alone, penniless, unassisted, uncomplaining. He is not a communications man, a disaster for a sponsor. He seems to do the anti-personality on purpose. So we find him in the winter of 2003 on a small dinghy, painting the hull of the 1985 trimaran, formerly owned by Olivier de Kersauson, in the colors of a sponsor he finally managed to find, Idec. With this boat, without any modifications, without the help of anyone ashore, much less a meteorologist, Joyon sails around the world alone in 72 days, nonstop, shattering the previous record set in 1989. The evening after his arrival, he does not join in the festivities; he is on the roof of his house replacing the tiles that winter had taken away. A year later the record will be broken by Ellen MacArthur. By a single day. In 2005 he also wins the Atlantic record, but shortly afterward his old trimaran crashes on the rocks at Pointe de Penmarc’h in Brittany. That’s his luck. Francis Joyon loses the boat, but he has found a sponsor, Idec, who asks nothing of him except to do what he knows how to do, go for the oceans. And try to break the solo round-the-world record again, which MacArthur snatched from him.

The incredible enterprise is born

Thus in 2006 the 2007/08 World Tour project came to life. Joyon finds himself having, for the first time in his life, a real professional team supporting him. And finally a new trimaran built just for him, the way he wants it. No longer will he have to sail on a ferrovecchio. The design is entrusted to the French-English duo Benoit Cabaret and Nigel Irens. They are the ones who designed the boat with which Ellen MacArthur beat Joyon in 2005. To make the new Idec a winner, on paper, they play on length and buoyancy. On Ellen’s boat (Castorama) they had already lengthened the hulls: three meters in front and one meter in back. Given the good result this time they dare even more. Idec will be a full 29.70 m long compared to Castorama’s 22.90. The hulls will be even longer and, above all, as fine as a knife blade. The critical point of an oceanic multihull is longitudinal stability, the more length you can put in the front the better. On the British sailor’s boat, the designers had focused on this aspect and succeeded in increasing safety, especially during dangerous sailing in the South Seas. On Idec, Cabaret, and Irens, they decide to go even further: they work on wave passage in formed seas. They reduce the water resistance of the hulls, aiming to increase speed, which also improves sailing in rough weather. Skippers in rough seas reduce sail to decrease speed, but when they enter a big wave, traditional multi’s tend to experience real “braking” by planting their hulls in the cable, with the risk of capsizing “from stern to bow.” On Joyon’s new trimaran, an attempt is made to delay as much as possible the reduction in the canvas and thus in speed, moving the dangerous “braking” further out. But there’s more: when Idec’s very fine center hull later penetrates the wave, the designers want it to exit more smoothly, slipping in and out a bit like a bottle cap does, accelerating. All this had never been realized concretely on such long hulls. In computer simulations Idec is not the fastest possible hull when the sea is flat, but it is incredibly fast and safe when the sea is very big. And it is proven, around-the-world races are won in the stormy South Seas. The design bet is big. On theoretical models, designers think Joyon can beat the record by three, four days at most.

Finally there is a routeur

For the first time for the 2007/2008 Idec project, Francis can finally count while sailing, in the hunt for the record, on the help of the world’s best ocean weather specialist, Jean-Yves Bernot, known as the Sorcerer. In his 20-year career, he has assisted the best French and foreign racers for the most prestigious regattas (Figaro, Vendée Globe, Volvo Ocean Race, etc.) and is the author of numerous books on the subject of weather. An experienced racer, he has been racing for more than 20 years on any boat that has one, two or three hulls. He was the architect of the French victory in the Admiral’s Cup. And he was on board during two round-the-world races in recent years (The Race and Volvo Ocean Race). His motto for records around the world is ” Go as little as possible, always. With any sea “.

No engine on board

Joyon relies for the first time on experts in each field. On one thing he is adamant and decides: he does not want a generator on board to produce energy. He relies on a wind generator combined with solar panels and a fuel cell. On arrival he will explain this ecological choice of his well: ” The system worked wonderfully, and I had the impression that I was not polluting. Also, the engine makes noise. You have to run it for at least two hours to recharge the batteries. I find this harmful. In the south I was happy that everything was fine and that it was not me who was altering an environment that remained as it was at the origin of the world. I left no trace, no residue. It was a great satisfaction to sail without polluting, never “. Plus it saves about 400 pounds of weight.

Joyon The utmost simplicity

The French navigator during the design did not put his beak on anything unless asked for an opinion. Except on the equipment and cockpit arrangements. Joyon, wanted everything under the banner of maximum simplicity, mindful of the teachings of the greatest sailor in history, Eric Tabarly. No extra electronic instrumentation beyond what is strictly necessary, on Idec there is nothing more than what is installed in a ten-meter cruising yacht. The maneuvering and command cockpit he wanted as small and simple as possible. ” The limitations are also budgetary,” explains Joyon “But above all, I have become accustomed to sailing with little. Reducing the material means reducing the risk of breakage and decreasing the weight “. The dimensions are 2.15×1 meter wide, very small. One wheel, four winches, everything within reach. The mainsail reduction maneuver did not want it deferred in the cockpit, but placed at the foot of the mast. A curiosity, Joyon has the same rudder wheel installed on the trimaran of his previous record. Superstition?

Joyon Training does not exist

The 51-year-old round-the-world navigator does no special training. “I have been spending multiple months of the year on the high seas for years now. I know I have to make my boat go as fast as possible, and what I like best about a multihull is that it is the fastest sail there is. These superboats glide on the water and are in harmony with the elements. i” he sentences.

It’s time to leave

Everything is ready. On Nov. 23 at 10:05 a.m. Idec crosses the starting line and sets off on a round-the-world voyage passing the three hypothetical capes: the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa, Cap Leeuwin, an eastern offshoot of Australia, and, after circumnavigating the Antarctic, rounding Cape Horn, the extreme edge of South America. We review directly with Joyon the key moments of his incredible ride across the globe’s oceans.

Nov. 30: The Equator

6 days, 16 hours, 58 minutes: never had any boat, even a crew, reached the Equator so fast in the history of offshore racing. “I feel that I have already covered the distance equivalent to that of an Atlantic crossing, and in reality I am only at the beginning of the journey. I am already homesick for my children and dreamed of telling them this little story: I dreamed that the trimaran’s drift caught on the equator line and cut it off. Suddenly all the parallels of the globe had no support and the planet began to warp. That’s why at the crossing of the equator to be on the safe side, I raised the drift and thought, what could be more beautiful than a child’s laughter scattering across the sea as you tell him a story? “.

Joyon Dec. 12: Record

“I had no intention of trying to break the 24-hour sailing speed record (616.07 miles at an average of 25.66 knots per hour), but I was in a favorable weather condition to walk as much as possible. I was facing a front that allowed me to sail 600 miles a day, thanks in part to perfect seas. The flat front was catching up with me, so I had to try to accelerate as much as possible. The record was just icing on the cake. “.

Joyon Dec. 19: Midway

“I pulled an edge to mount above 52° south and then descended as fast as I could so I wouldn’t get caught in the weak winds behind me. Great, the barometer begins to drop again. That’s the interest of a fast boat like mine: playing with the elements, putting yourself in direct relationship with them. I am happy to have reached the halfway point. Now the Pacific begins! “.

Dec. 24: Among the Icebergs

“I had some luck at the 56th level with icebergs and no visibility. I saw four after spending an infamous night in a storm. I was four miles from the nearest one and could see nothing, blinded by the rain mixed with hail; luckily there was radar. I zigzagged between them, concentrating on watching the water for growlers (semi-submerged drift ice chunks, ed.). I know well an all-white Christmas spent like that. It had happened to me four years ago. It’s amazing to think that I sail among icebergs, bits of Antarctic wandering around the sea.” .

Dec. 25: Storm

“Onde of 7 meters steady wind on 50 knots. I realize that in this weather there is no need to have canvas on shore. I sail at 20 knots with the mainsail down! Removing the mainsail was a huge effort and I am taking on fatigue. I am at 80 percent of what I can do “.

Joyon Jan. 11: Failure

“I went up to the masthead to pass a new mainsail halyard and realized that the starboard rigging attachment is unscrewed. The boat bangs so hard that I smashed into the mast, injuring my ankle while trying to repair the damage. The situation is dangerous. I have reduced the sail and tensioned a halyard on the starboard side, in case the rigging attachment does not hold. Hopefully the weather will improve to make the repair. In the meantime, I am sailing at a reduced speed “.

Jan. 16: Repair

“I finally went up to the masthead and, as the mast builder told me, hammered on the rigging attachment. Then I made a tight tie around the mast with some Spectra line. I am comfortable “.

January 21: Arrival

“I am tired and exhausted,” he declares after crossing the finish line at 12:40 a.m. At the dock in Brest thousands of people are waiting for him. He stays on board, gets taken to the mooring, and goes to sleep in the damp bed of his boat. For interviews there is time in the morning.

by Luca Oriani

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

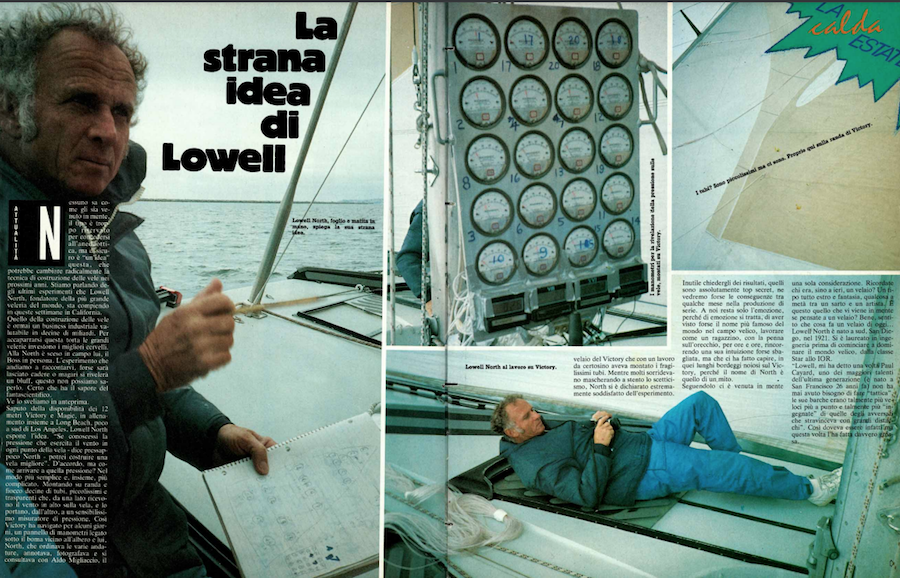

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions