2013. Chichester, the first hero of ocean sailing

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

Chichester, the first hero of ocean sailing

Taken from the 2013 Journal of Sailing, Year 39, No. 06, July, pp. 58-63.

The incredible story of Sir Francis Chichester who in 1966, at the age of 65, boarded the legendary 16-meter ketch Gipsy Moth and set out on a nonstop solo round-the-world voyage. He made it in 274 days, becoming the first hero of ocean sailing .

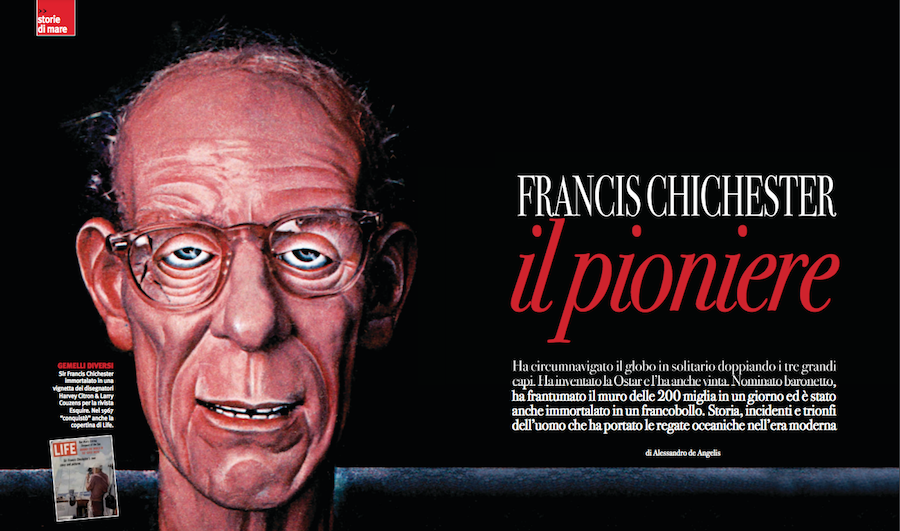

He circumnavigated the globe solo, rounding the big three capes. He invented the Ostar and even won it. Named a baronet, he shattered the 200-mile wall in one day and was also immortalized on a postage stamp. History, incidents and triumphs of the man who brought ocean racing into the modern era.

The incredible story of Sir Francis Chichester who in 1966, at the age of 65, aboard the legendary 16-meter ketch Gipsy Moth set out on a nonstop solo round-the-world voyage. He made it in 274 days, becoming the first hero of ocean sailing. He circumnavigated the globe solo, rounding the big three capes. He invented the Ostar and even won it. Named a baronet, he shattered the 200-mile wall in one day and was also immortalized on a postage stamp. History, incidents and triumphs of the man who brought ocean racing into the modern era.

A life that reads like a 19th-century adventure novel, that of Francis Chichester. He did everything and succeeded in everything, overcoming serious accidents and illnesses, until he earned the title “Sir,” he who was born on September 17, 1901 into a family of modest origin. He lives a miserable youth; his father, a pastor in the Anglican Church, sends him as early as age six to boarding school, from which he does not leave until he reaches university. After attending Marlborough College during World War I, he emigrates to New Zealand. There he discovered his first great passion, flying, and took his pilot’s license. At the same time, Chichester shows that he has a good nose for business and creates from nothing a solid company active in mining, timber and construction.

The return and the discovery of the sea

Everything seems to be going great, but suddenly the Great Depression of 1929 arrives, causing huge losses to the Chichester company. He then decides to return to England, where he also has to pick up a de Havilland DH.60 aircraft Moth. It is a biplane of just over seven meters, with which he plans to fly to New Zealand. He wants to break the record for flying solo from England to Australia. He failed to achieve the record, but still completed the crossing in 41 days. In compensation, he is the first man to fly over the Tasman Sea. To accomplish this, he applies real maritime methods to the flight: for example, he follows the magnetic course without correction. Once the estimated distance is reached, it veers to find the arrival point. A technique that allows him to find the end point with a precision previously unknown. On the strength of these innovative techniques, Chichester attempts a solo round-the-world tour. The first leg, to Japan, proceeded smoothly, but starting from the port of Katsuura Wakayama failed to avoid cables and crashed, seriously injuring himself.

Chichester creates the Ostar and wins it

The return to England is obligatory and even becomes forced with the outbreak of World War II. Chichester is not skilled in field service, but he puts his knowledge to good use as a navigation expert: he writes a manual to help single-seater drivers find their way over Europe and then their way home, based on charts that are still in use today! It was only many years after the war, now almost 60 and well off thanks to the creation of a thriving map-making firm (could it be otherwise?, ed.), that Chichester’s interest shifted to the sea. In 1960 here was the insight: he organized the Ostar, the first transatlantic race for solo sailors (the last edition of which had just been held). But organizing is not enough for him; the lure of challenging himself, strictly on his own, is too strong despite his advanced age. Chichester appears on the starting line aboard the Gypsy Moth III. Like his planes, all of Chichester’s boats are also named Gypsy Moth, which literally translated means “flying moth.” He not only participates, but wins, then coming second four years later.

The world tour

But the feat that enshrines Francis Chichester is yet to come. On August 27, 1966, in front of the town of Plymouth, he boarded the Gypsy Moth IV. He is about to turn 65 and wants to circumnavigate the globe by rounding the three great capes: Cape of Good Hope, Cape Leeuwin and Cape Horn. Succeeding, he would surpass the legendary Joshua Slocum, who at the turn of the century had taken three years to succeed in the feat, albeit without passing all the bosses. The Gypsy Moth IV, at sixteen meters in length, immediately proves difficult for Chichester to maneuver, despite the fact that it was armed specifically for this navigation. The sail plan includes about 80 square meters of white-sailed canvas and a 140-square-meter spinnaker.

Between gales and triumphs

In the first phase of the circumnavigation everything seems to be going according to plan. But problems are not long in coming. We are still 2,300 miles away from passing Australia when a rudder problem makes Gypsy Moth IV seemingly unsteerable. Chichester did not lose heart and spent three days trying to find the correct sail trim to be able to stay on course. He succeeds and, traveling about 160 miles a day, reaches Sydney. Here he stops to repair the damage and try to improve the stability of the Gypsy Moth IV. An attempt that actually, as he would discover shortly afterwards to his cost, fails. In the South Pacific, a wave capsizes it at 140 degrees, but fortunately without leaving irreparable damage. And the terrible Cape Horn is yet to come. “The waves were tremendous. They changed each time, but all of them anyway were like walls looming up behind you. The one I liked the least was fifteen meters high and very steep. Imagine being under a wave like that. My cockpit was flooded five times and in one case it took me a good quarter of an hour to empty it. The anemometer stopped registering at 60 knots. My rudder could do nothing…. I felt helpless.” Yet Chichester succeeds. He also crossed the Atlantic, and on May 28, 1967, 274 days after his departure, he returned to England, hailed as a hero. The feat earned him the title of Sir, in a festively decorated London. Queen Elizabeth II uses for the ceremony the same sword used centuries earlier to knight another Francis, the famous Drake, the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe. Despite his success and age, Chichester is unwilling to sit still, and in 1970 he managed to travel 1,000 m ly in five days, in the Caribbean Sea, thus proving that it is possible to sail over 200 miles a day. He died in Plymouth, of lung cancer, on August 26, 1972, after charting the course of modern ocean racing and relaunching the hunt for records around the world. But also some phrases that remain mythical in the world of sailors. Like that day when, loading crates of gin onto a boat, he let loose: “Any fool could sail around the world, but it takes a sailor with the attributes to be able to do it drunk.”

by Alessandro de Angelis

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

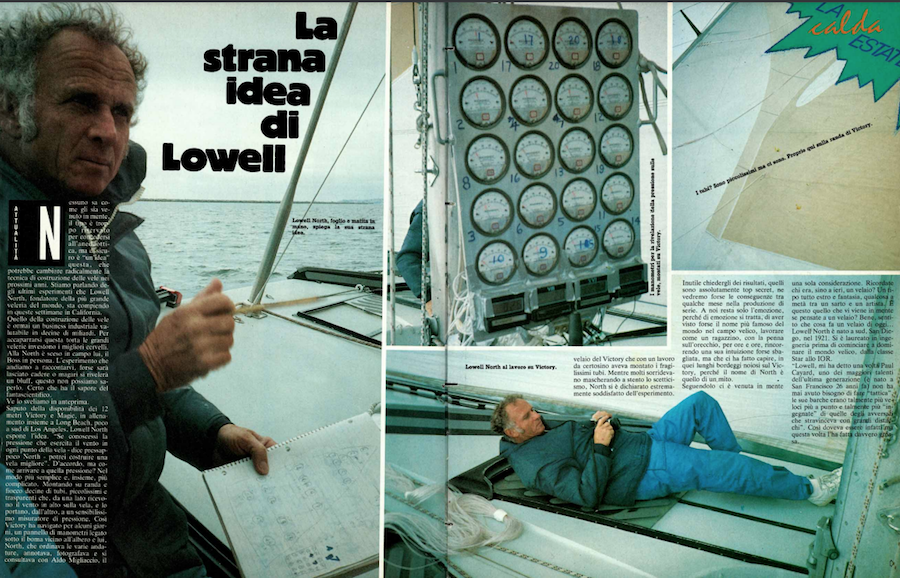

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions