2023. What is a storm in the Mediterranean

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

What is a storm in the Mediterranean

Taken from the 2023 Journal of Sailing, Year 49, no. 02, March, pp. 88-91.

Vincenzo Onorato was there with his boat in November 1995 when the racing boats were hit by one of the most terrible storms in Mediterranean history. Onorato’s gripping account from aboard a Swan 59 in the Gulf of Lion. The boat saves the crew but pays the price of destruction.

There was the French bulletin erupting cyclone or maybe less…yet in San Remo there was flat calm and too much sunshine to fry the sea with the mercilessness of a preemptive repentance as fetid and festering with the leesy of an extreme trap. Storm? And what is a storm? In the pale blue sunshine of a still-unbleached November, which had us walking around the dock in late June T-shirts and even sweating with voluptuousness because it was not the season to sweat, the vaticinium seemed absurd. And then there was the regatta, where the demon had invested all its mischief. Man is equal to God, without, of course, leaving room for the idea that the sea is certainly God’s and God’s is, perhaps, albeit minimally, man’s if he chooses to be, who kneels before his own limitedness and turns his eyes to heaven in search of help and inspiration. However, eventually we set off, talking up the oncoming storm with a genoa light on the bow that seemed to contradict every blackest prediction, and faithfully serve the racing demon laced with the venom of our own skepticism. There was talk of closing the course under Toulon and paying due bows to the Lion and its mistral, a furious beast predicted by the weather. Yet the committee, heedless, had set us off, in agnostic French indifference all boats went by course without bowing to fate. And we don’t? Were we supposed to be the most careful and lame? We, just we, a crew sailed in one of the best boats in the fleet, a Swan 59?

Horror is always lurking

The seduction of the racing demon posed a question to us all to arouse our irrepressible pride: “What is a storm?” Forty, fifty knots of wind and we answered in unison as if drawn by an ancient and never resolved call in the temptation of challenge: already seen! And so we pulled straight, strong, full of ourselves, proud of the choice, deliberately aware of our destiny but above all drunk with ourselves. Yet a parasitic woodworm devoured our soul more than our ego: what about the storm? What if it is really coming? But the weather was beautiful and the sunset poignant on our bow irradiated by the dying sun and guided by minds wracked by the sin of our irrepressible egos. Horror always lurks in the lives of men and is preceded by a tranquilizing flat calm. And at night exploded the mistral, first treacherous and calm, 15-20 knots, containable, comforting then rising to 50 knots and bending our truncated pride of sin. We had lowered the mainsail and were proceeding with the mainsail that had replaced, without compromise and awareness, the genoa light. Then the mistral mounted unstoppable and fierce, 50 to 60 knots of wind, and the waves rose and grew merciless against us. The air around us misted like a shroud of water to bury our guilt. We responded to the storm with the professionalism acquired over many years at sea: we spread a “life – line” stern – bow, a steel cable to sling to with a belt and two carabiners securing people on deck. Two above and the others below in the dinette where everything was upset: the genoa light to clutter the room and the wheel of parmesan cheese carried with venerable care to support the crew destroyed and smeared on the bulkheads like a cream whipped up by rolls and made sour by vomit. I had never suffered the sea and mocking the so-called “vuommaca mare” (Ponzese slang for those who suffer the sea…), I was harnessed with a strap to the chart table desperately trying to make with the Loran, at the time there was no GPS, the ship’s point and then report it on the chart. Along came the distraught doctor who grabbed onto the chart table and shouted, “You’re all crazy! We’re going to die!” And I replied, without not having first looked at the true wind speed which read 75 knots of wind, “Nooo, when it marks that strong it passes quickly!” And then he threw up on the chart table, on the chart, my oilskin and my face. I instinctively wiped the paper with my right hand to save it from the infinite acid but the gastric effluvium proved fatal for me. Before the boat capsized my stomach churned: I detached myself from the seatbelt that kept me anchored to the chartreuse and rushed outdoors. I begged Marco to hold me by the pants and leaned over to throw my soul back underboard heedless of the cyclone’s rush. Then I rushed below deck to continue vomiting prostrate in the dinette already filled with humors and my frustration. Then the boat lay down several times and offered its side to the waves.

The waves grow merciless

Downward everything flew everywhere and then again, after the night, came the rosy-fingered dawn to open our eyes to the hell that awaited us. We tried to regain our strength and reason: first response was to lighten the boat. We began to empty the tanks and throw overboard whatever we could to make it float. Sails, provisions, everything, even the pots and pans and personal belongings, and then exhausted we went back to puke trying to establish two-man guards attached to the life-line to steer the boat and keep it stern to the storm. We deluded ourselves, yes we deluded ourselves, that we had regained control of the situation but then came the bruising and freezing sunset with the wind that made no sign of abating as the waves grew merciless to give our astonished eyes a glimpse of what the abyss of hell looks like, where there was no fire but water, and more water, to flog our now already distraught minds. Night fell, the second, and the wind increased again beyond the unimaginable, the possible and the sense of fate. Off deck Daniele, a big sailor, was at the helm and Alessandro, a big Elban boy, in the cockpit. We were below deck, suddenly the boat lifted, as if floating in the uncertain as well as violent air, and then plunged into an abyss and folded, toppling upside down. The dunnage flew into the sky, and from the skylight above the dinette exploded a tall fountain of water from its one-square-meter perimeter. We had no time to be appalled: we crushed under the dinette sky were bleeding from the dunnage that had crashed down on us.

“Alexander flew overboard!”

crew members huddle around the improvised raft, but the cold and many hours in the water get the better of them. They thus slip into the sea, one by one, Luciano Pedulli, Daniele Tosato, Mattia De Carolis, Giorgio Luzzi, Francesco Zanaboni, and Ezio Belotti.

We did not notice that the pitiful and superb boat, stronger than we were, straightened up until the heavy wooden dunnage came crashing back down on us again to batter us. But it was short-lived: we seemed for a moment to stabilize until we again felt with horror that sense of emptiness and ascent that preceded the precipice but this time she seemed to plunge straight ahead into the abyss andshe scuffed, yes, she scuffed bow-first and then, then , then she twisted upon herself like a wounded whale and bent again, we plummeted again and toppled over; and again the hsteriggio showered us with a square, perimeter fountain of water and in horror the dunnage struck us again mercilessly, sending us flying everywhere without more, in terror, feeling the wounds and pain. And again the boat wanted to save us by righting itself, we seemed to breathe until we heard, in the howl of the wind and waves, a cry that had nothing human about it coming down from the deck. It was Daniel, like a rumble of thunder, “Come out, in the name of God, Alexander has flown overboard!”, “Overboard!”, “Overboard!”, “Overboard!” A shocked echo still indelible in our memory. And so we rushed out, heedless of the danger and I could already see myself having to explain to his parents about losing their son at sea. Certainly that was everyone’s thought, and so we went outside, not tying ourselves down, not caring about anything but the despair that more than the wind and the waves unsettled our lost souls. And we saw the luminescent stars of the mistral that always announce death with the irony of a superb beauty, we saw the merciless waves that compared to the crosses of our mast were 14-15 meters at the crest and obscured the stern, short-stepped and cruel, mountains of water that chased each other without giving us a break. The boat had capsized and the carabiners that kept Alexander anchored to the life – line had split open like butter from the weight of the boy’s hundred pounds. We tried to start the engine, and it started, then a wave covered us making us think we had sunk.

Rising from the abyss

Then the boat resources from the abyss into which it had plunged but it was a moment and we plunged back into apnea covered by a mountain of water. We rose again in the madness of the delusion that we did not want to lose Alexander and turned the boat around, offering the bow to the sea in the breathlessness of despair. The rest is an act of God even to those who do not believe in miracles, and this is a manifest provocation to atheists and agnostics. Alexander, like a skilled swimmer, had shed his oilskin and despite having a fractured arm, lit a lamp he kept in his jacket. We went upwind by God’s will, and after a couple of tries Marco, Roberto and I got him back on board.

His condition was desperate and we had to give him aid. Alexander had a fractured arm and shoulder and was bleeding profusely. We tried to make a point ship, without having any certainty. We had to be upwind of Mahon somewhere…maybe…Putting us back to windward had exhausted the last of the boat’s energy and we had no more engine and electricity, everything was broken except the mast that towered still swinging between the waves and the sky like a pendulum gone mad. And dawn came again, rosy fingers, reminding us that in spite of everything we were still alive. We contacted with the portable VHF the port of Mahon, which sent a patrol boat to escort us to land in the windward fjord where very high waves crashed in the howl of the storm and where we would inevitably break in the absence of a certain goal. We maneuvered, without engine or sails but only with the science of desperation and an ambulance greeted Alexander. We left the boat without thanking her and fled to the nearest hotel. I slept a dreamless, showerless sleep. The next morning we all met for breakfast. I was urinating blood, probably from all the blows I had taken below deck. Someone asked if we had continued the regatta. I did not respond, however we seemed to be unaware of what had happened.

Everything was as still as in a photograph

We went to the hospital to find out how Alexander was doing and were reassured about his condition. We went down to the harbor to fix up the boat. It was always very windy, and the boat was moored at the English dock where we had landed less than twenty-four hours earlier. We saw the clear sky and small clouds rushing westward, we saw the sun blinding us like an unbearable insult to remind us of our presumption, we saw the innocent contours of the canal watching us indifferently, we saw the pitiful dust kicked up by the wind trying to hide the horror from us, we felt the deafening silence of death envelop us until it cut off our breath, we saw the houses of the fjord rushing down on us a moment before we saw the bodies of the Parsifal boys bagged on the pier made livid by our disbelief. And then we glimpsed the bottom of hell, worse than the chaos of water and wind of the storm, because silent and final, where there is nothing more to say or do but just wait for that image to macerate in the heart in future decades to haunt our souls. Everything was as still as in a photograph, and time seemed to have stopped its course. We could feel our breath coming down to chill our bones. Incapable of any reaction in silence we went aboard our boat and, without any order, in silence, we instinctively began to wash it as if to give some sense of reality to that nightmare we did not want to believe. The boat had saved us but had paid the extreme price of being destroyed, and the water, from the deck, descended from below as the pain in our hearts; suddenly, in silence and without saying anything to each other, we all began to cry at the same time, without looking each other in the eyes. A memory that will haunt us for a lifetime and perhaps, or probably, beyond death, if death really exists.

by Vincenzo Onorato

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

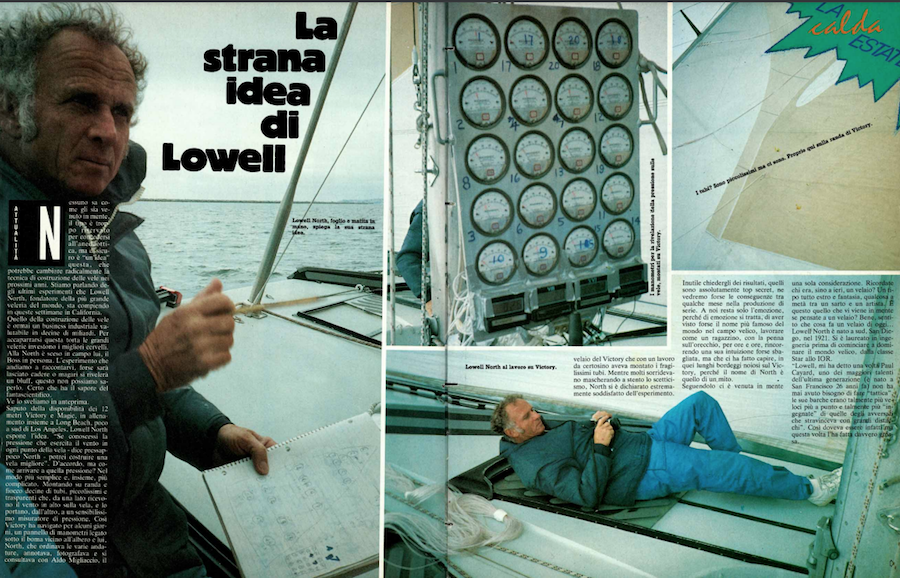

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions