2004. Aboard Joshua, Moitessier’s legendary boat.

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

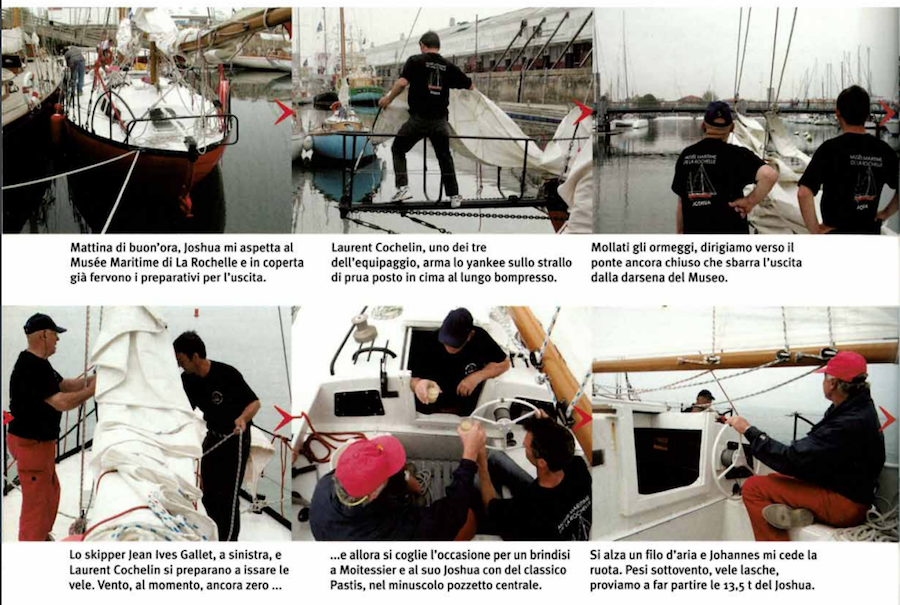

A Day with Joshua

Taken from the 2004 Journal of Sailing, Year 30, No. 11, December-January, pp. 48-57.

We sailed on Joshua, the legendary boat in which Bernard Moitessier in 1968 abandoned the first solo round-the-world race to reach Tahiti and become sailing’s greatest poet. Joshua is one of the most absurd and surprising boats in history. Let’s get on board together.

Ten years ago Bernard Moitessier died. To remember him we went sailing on his legendary red ketch, now owned by the Musée Maritime in La Rochelle. A truly emotional experience…

The day is not the best for sailing. In spite of its reputation as a windy sea, the North Atlantic this morning seems downright sleepy. No matter, the excitement of boarding the Joshua of Bernard Moitessier, the curiosity to discover its secrets live, overshadow the predictable lack of wind. As I approach the Musée Maritime in La Rochelle, I catch sight of her red hull moored amidst a crowd of classic yachts, also guests of the Museum. Joshua rests in good company, at the stern is one of Chichester‘s earliest boats, alongside a pair of splendid schooners from the early 1900s, and all around a multitude of beautiful, strictly wooden hulls, including some old French Dundées and English Gaff Cutters, which could tell a century of seafaring history. It may be because I read what this ketch managed to do that was extraordinary in her previous life, the one spent with Bernard. But even with the conspicuous dents caused by the wreck in Mexico, she looks to me like an albatross among a flock of swans. She has that proud dignity of boats made for sailing, where the lines seem drawn by the sea and every detail has its own precise logic. Joshua was designed by four hands in 1960 and it took 14, months before Bernard gave the okay to Jean Fricaud ‘s Meta shipyard to begin construction, in which he personally participated.

A cost-effective operation

It was a great demonstration of solidarity and love for the sea: so was that of Jean Knocker, the designer, who freely offered to bring Bernard’s ideas and sketches back into architecturally correct form. And so was that of Fricaud, who at the sole living cost of iron sheets and welding rods built in just three months the Joshua. Both, reading Moitessier ‘s book Cape Horn to Sail, had been fascinated by the character and his adventures. The operation, in fact, proved cost-effective: of specimens of the Joshua as many as 70 were made, some of them of recent construction. Looking at this Norwegian stern-rigged ketch, the only one according to Bernard capable of “dividing, directing and cushioning to a large extent the violent thrust caused by a breakaway crest in a breakaway gait, “ I am struck by the height of the very low freeboards, a mere 75 cm amidships. Like a tugboat, the hull goes all the way underwater with a star-shaped long keel hull ending in the outer rudder blade. The mighty bow houses a tubular bowsprit a couple of meters long, supported by two stays and winds and reefs made from 12-gauge chains. In resting my foot on the foresail, the boat does not even feel my weight. Rock. I climb over the webbing, also made with chains and painted black because, as Moitessier claimed, they are more visible at night. And I finally climb aboard. Welcoming me is the current skipper of the Joshua. Jean Ives Gallet, while the two co-skippers Laurent Cochelin and Iohannes Raymond are already at work rigging the sails. “We have to leave right away,” Jean Ives tells me, “the deck opens soon and the tide is good now.” Incidentally, the tide today has a 5-meter excursion, so leaving and returning are dependent on its timing.

Free on the sea

Meanwhile,Patrick Schnepp, director of the museum and a longtime friend of Moitessier‘s, arrives. It is to him that we owe the initiative to bring back to France Joshua. In 1990 he managed to get it resold by an American lady who in turn had bought it from Joe and Neto, the two young men to whom Bernard, left penniless, had given it after it was shipwrecked on the coast of Mexico. Moitessier had supported the idea, collaborating in restoring Joshua as it was in his day, including the two masts made from telegraph poles. He had dictated, however, “not to set her up like a trophy in a bottle, but free on the sea with new sails.” Schnepp kept his promise. Joshua already for years has been available to the public (for contacts www.museemaritimelarochelle.fr), when he is not engaged in the circuit of historic boat races including the very famous one held in Brest. We are about to cast off our moorings but from the dock a woman shouts at the top of her lungs to stop. It is Isabelle Autissier who has to do some filming with French TV operators at the interior of Joshua. Of course, back up and tops tightened again. Isabelle is at home on Joshua, from time to time she comes to rim it, to sail on it and would like to do so again today. But journalistic duty calls her elsewhere. After a good quarter of an hour we manage to cast off our moorings again and motor toward the dock exit. First bridge, then the second, we pass between the two ancient towers of La Rochelle harbor and arrive in the open sea. Wind at the moment zero, however we hoist the sails: main, mizzen, both with three hands of reefing, yankee and foresail, also reefable. All new but as at the time very heavy, the lightest being of 10-ounce fabric. And to think in his early years, including those that took him from the Mediterranean to Tahiti and then the terrible return via Cape Horn, Joshua sailed without halyard winches or sheets. Bernard capped the sails with flying hoists, and it was not until the Globe Challenge, the first ’68 edition of the nonstop round-the-world race (today’s Vendée Globe), that the boat was fitted with four winches donated by Goiot, two of which are still aboard. Instead, the winches remained for the main and mizzen sheets, two for each sail so the leech could be better adjusted upwind. The engine, which is not the original 7 hp but a more modern 40 hp, stops mumbling and we stand still in the silence of a somewhat misty atmosphere. We have all morning to spare, sooner or later some air will rise! Meanwhile, glasses go up from underneath, 10 a.m. toasting Moitessier with Pastis, all four of us gathered in this tiny cockpit with high, admittedly uncomfortable backs.

A system as simple as it is effective

I start looking around, observing the boat in detail. The first one that jumps out at me is the wheel steering circuit, with the brakes running free on the deck. A system as simple as it is effective. “Bernard originally thought of it that way for the inside wheel,” says Johannes, who got to know Moitessier and sail with him , “then he added this second wheel in the cockpit.” Meanwhile, a breeze picked up. 5/6 knots from the southwest. Johannes leaves me the wheel. In spite of its 13.5 tons displacement and its wet surface, as well as a fixed three-blade propeller that is a plow, the boat begins to move with surprising ‘agility. Then again, there is plenty of canvas; the mainmast is 16 meters high from the water’s surface, and to this must be added the mizzen mast, for a total of almost 110 square meters of sail area upwind. So much, to the point that the designer himself had expressed some misgivings about her maneuverability when solo. But Bernard had been adamant on this aspect: “maximum canvas and fractional sails.” With the result that Joshua is a very physical boat. “I wonder how he could handle her alone,” Jean Ives tells me , “when it’s windy we struggle to carry her in three.” And indeed maneuvering four sails without any aids (see furling) and with minimal equipment. must be no joke. On the choice of ketch rigging, Bernard will in time reconsider: “If I were to rig Joshua again … it would be a cutter,” he writes in Tamata and the Alliance , “less burdens and weights up top, a freer deck, better upwind performance …” Yeah, upwind. The feeling I get at the helm is not of a very upwind boat. Then again, in addition to the ketch rig, there is a relatively low drift plane, intended to be able to enter the “passe” of the Polynesian islands. The boat fishes meters 1.60, and it is known that a shallow keel is not the best for going upwind. As for course stability, though, hard to get better. If I leave the wheel Joshua goes straight as a spindle, and this, especially for a boat designed to sail with a windward rudder, is an essential peculiarity. That of Joshua was a small flettner, a kind of airplane flap, mounted on the same blade as the rudder. There are still flettners. Upwind wide toward theIle de Re, Joshua spins at 4 1/2 knots in 7 to 8 knots of wind. He comes alongside a Dufour 38, greets us and attempts to overtake. He will need a good half hour to catch our bow. He speeds up and slows down on every slight change in the wind, while we keep going at the same pace. On the way back to La Rochelle, Jean Ives tells me that the week before there was a regatta with a sudden 50-knot gust of wind. Some boats dismasted, others broke sails and equipment. Joshua made it to the finish line intact. And first in his class.

An incredibly reliable boat

Moreover, the reliability of this boat is proverbial; it has endured stresses of all kinds by sailing along the world’s most challenging routes. And it has always fared well. Like that time in the South Pacific when she faced the most violent gale of her life. Moitessier in his Cape Horn to Sail describes it this way, “And Joshua always ran with confidence, under the 15-20 degrees of his golden rule, under the waves that sometimes passed over the wheelhouse dome, in a huge sea that had become supernatural.” Bernard ‘s spirit still hovers over this ketch, aboard we seem to feel his presence. Greeting Joshua, motionless at the mooring, as at the end of the Long Course, he meanwhile “listens to the sea.”

Who was Bernard Bernard Moitessier

Navigator, writer, philosopher. Also cabin boy, farmer, shipwright. But above all, dreamer and idealist. Bernard Moitessier bequeathed us his knowledge of navigation, as well as his utopia and wisdom as a free man. A man who, despite the adversities that fate dealt him, always managed to rise up. One has to read any of his books, from A Wanderer of the South Seas to Cape Horn to Sailing, from The Long Course to Tamata and the Alliance, to discover the complexity and spirituality of his being. But for many Moitessier also represented an example of how one can practice sailing without being rich, sail around the world in a “minimalist” boat, and live on the sea by making do. Born in 1925 in Indochina, Bernard learned sailing from fishermen. In ’51 he bought an old fishing boat, the Snark, with which he sails in the Gulf of Siam. The following year it was the turn of Marie-Therese, a junker he restores and with which he sets out on his first solo adventure. He wrecks in the Chagos Islands, reaches Mauritius, and over the next three years builds his third boat with primitive tools, Marie-Therese II. In ’55 he left his moorings and sailed to the Caribbean, where he suffered his second shipwreck. Meanwhile he publishes his first book and with the proceeds builds his third boat, the Joshua. In ’63, he sailed with his wife to Tahiti and after three years returned to Europe via Cape Horn. Always with Joshua in ’68 he participated in the first nonstop solo race around the globe: he was first at the last “rounding of the buoy” but decided to abandon. He launches a message with his slingshot to a ship he crosses: “I go on nonstop to the Pacific islands because I am happy at sea, and perhaps also to save my soul.” He arrives in Papeete after one and a half rounds of the world without touching land. After the shipwreck of Joshua, he builds the last boat, Tamata. In the meantime he retires to live on Ahè Atoll. He dies in France in ’94.

by Leonardo Zuccaro

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

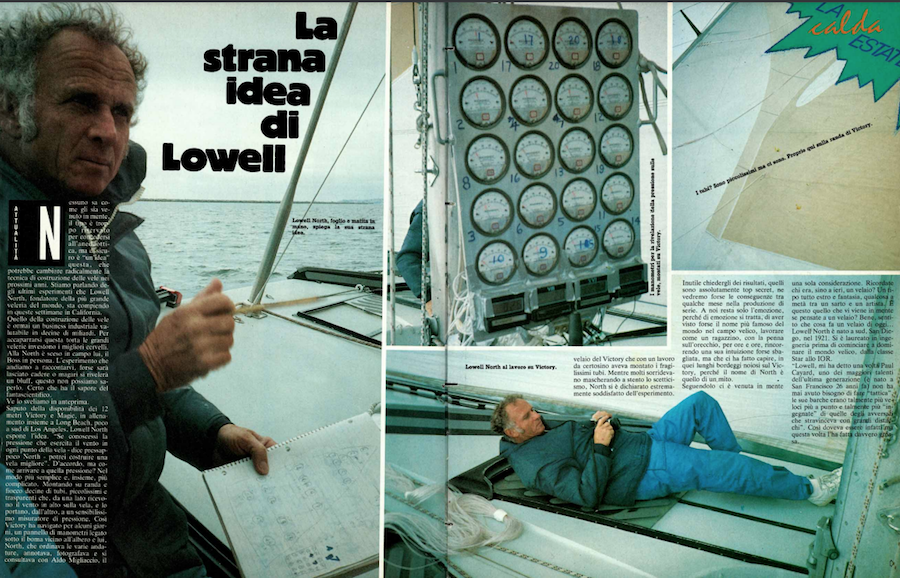

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions