1975. The father of the Laser tells how the most famous boat in history was born

THE PERFECT GIFT!

Give or treat yourself to a subscription to the print + digital Journal of Sailing and for only 69 euros a year you get the magazine at home plus read it on your PC, smartphone and tablet. With a sea of advantages.

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day with the most exciting sailing stories-it will be like being on a boat even if you are ashore.

The father of the Laser tells how the most famous boat in history was born

Taken from the 1975 Journal of Sailing, Year 1, No. 2, August, pp. 9/12.

Bruce Kirby, the designer of the Laser, recounts how from the idea of putting an easy-to-arm barque on the roof of a car, the most ingenious idea in the history of sailing was accidentally born.

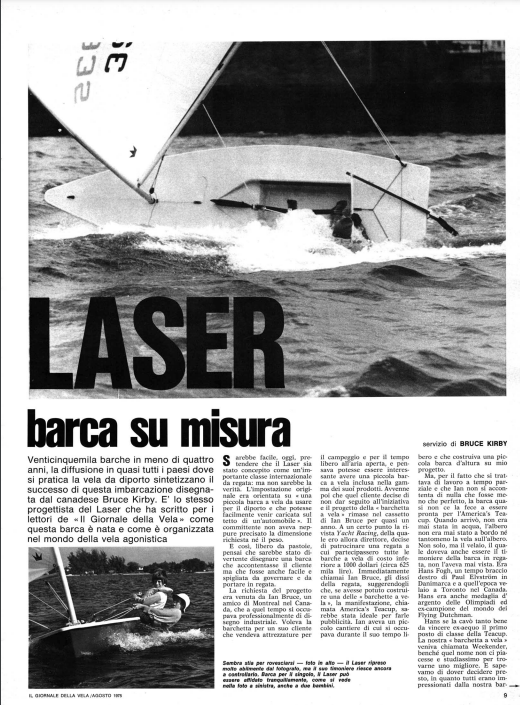

Twenty-five thousand boats in less than four years, spread to almost every country where recreational sailing is practiced summarize the success of this boat designed by Canadian Bruce Kirby. It is the same designer of the laser who wrote for readers of Il Giornale della Vela, how this boat came about and how it is organized in the world of competitive sailing.

It would be easy today to claim that the Laser was conceived as a major international racing class: but that would not be the truth. The original approach was geared toward “a small sailboat to be used for pleasure and that could easily be loaded on the roof of a car.” The client had not even specified the size required, nor the weight. And so, free of fetters, I thought it would be fun to design a boat that would please the customer but also be easy and nimble to steer and take to regattas. The request for the design had come from Ian Bruce, a friend in Montreal, Canada, who at that time was professionally involved in industrial design. He wanted the little boat for a customer of his who sold camping and outdoor recreational equipment, and he thought it might be interesting to have a small sailboat included in his product range. It then happened that that customer decided not to pursue the initiative, and the “little sailboat” project remained in Ian Bruce’s drawer for almost a year. At one point Yacht Racing magazine, of which I was then editor, decided to sponsor a regatta in which all sailboats costing less than $1,000 (about 625,000 lira) would participate. Immediately I called Ian Bruce, told him about the regatta, and suggested to him that if he could build one of the “sailboats,” the event, called America’s Teacup, would be ideal for advertising it. Ian had a small boatyard that he took care of during his spare time and built a small offshore boat to my design. But, due to the fact that it was part-time work and that Ian would not settle for anything that was less than perfect, the boat almost didn’t make it to be ready for America’s Teacup. When it arrived, it had never been in the water, the mast had never been on board, nor had the sail on the mast. Not only that, but the sailmaker, who was also to be the helmsman of the boat in the race, had never seen her. He was Hans Fogh, once Paul Elvström’s right-hand man in Denmark and at that time a sailmaker in Toronto, Canada. Hans was also an Olympic silver medalist and former Flying Dutchman world champion. Hans did so well that he won ex-aequo first place in the Teacup class. Our “little sailboat” was called Weekender, although we did not like that name and were studying to find a better one. And we knew we had to make up our minds soon, as everyone was impressed with our boat, a beautiful purple-red color, in the circles of that unique regatta, and we were beginning to suspect that the boat might turn out to be a big deal.

The Birth of the Laser

But back to the drawing stage. The instructions I received were that I was to draw a pleasure boat, pleasant even to look at. They were not such elements as to give me a starting point, but I allowed myself plenty of room for the use of my imagination. So I worked on the principle that a boat can be good for a leisurely ride in front of the beach, or to keep at the seaside cottage, but it can also become a very sophisticated racing machine for those who want to exploit it that way. So from the very beginning, the boat that is now the Laser was designed for this dual use: a fast, light hull, also to be more easily transported ashore, and rigid with modern, elaborate rigging. It had a laminated centreboard and rudder whose cross section was that of the NACA 0009 airfoil. And why not? A novice would not have noticed the difference while the expert would have fallen in love with it. It had a cunningham for adjusting the sail “grease,” intended for the expert, but for the non-racing enthusiast that selvedge was known as the mast restraint for capsize cases. It had a slider that the novice would avoid using, but which the expert could exploit; and a curved, unstayed mast, which for the novice was simple cheap but which in the expert’s opinion gave complete mastery over the shape of the sail. And even the sail itself was the best Hans Fogh could wish for, cut in the best dacron of the required weight that Bainbridge produced. Again, the novice could not tell the difference but took advantage of a good sail that would last a long time while the racer was impressed and satisfied with the cut and the quality of the sail.

Difficult decisions to make

There were many features of the hull capable of satisfying both the novice and the expert. The almost flat deck was originally designed so that children, perhaps three or four of them, could sit almost anywhere on the boat with the limited danger of slipping overboard, as can happen with a very convex deck. It turned out later that the racer was also pleased in that such a shape facilitated movement in both light and strong winds. The rookie was enamored with the safety of the small cockpit that was immediately dry after a scull, while the racer was also enamored because in high winds he took in very little water when the waves broke over the bow. There had been decisions to be made in the early stages of the project that I found difficult, much more so than those related to offshore boats. The main one concerned the crew to be used in proceeding with displacement calculations, calculations that in turn determined the overall shape of the hull. Was the boat to be made to carry two men of about 75 kg each? Or one man and his wife? Or two or three children. Or a grown man weighing 90 kg? A hull suitable for a 60 kg person would have been too submerged if a 96 kg man was at the helm. In the end I chose a crew weight of about 79 kg, which meant that someone weighing 90 kg would not be too heavy and someone weighing 68 kg would not be too light. Also it would have been fine for two children weighing 40 kg each or for a mother with her son. Another problem was related to the buoyancy reserve at the bow. I wanted a boat with a low freeboard, but a bow that was too low could have had a tendency to submerge when the boat was taken to sail vigorously, in high winds. Too much freeboard meant too much weight. If the bow was too full, the boat would be slow upwind and in light winds. Therefore the forward shape of the hull on the waterline was kept rather fine, while above that line it was very full. Partially this was achieved by drawing the foredeck 7.5 cm wide at the top thus making it possible to obtain an abundant waterline reserve without, however, exaggerating the overall length of the boat. The construction of the structure was entrusted entirely to lan Bruce who, with his experience as an industrial draftsman, had extensive knowledge of materials and their stress resistances. It was not possible, since these were boats to be built in series, to keep the weight down in designing 54 kg structures and therefore, after the first two prototypes, the weights rose to 56 and 59 kg: still lighter than others of the same size order. One of the secrets to achieving a light and rigid boat was the use of airex foam as the core of the deck and two strips about 15 cm wide of the same material along the bottom, lateral to the keel.

It will be called Laser!

Some of the most important work done on the boat was done after the America’s Teacup regatta. Ian built another prototype so we could try it out with the existing one. Then we tried various combinations of tubular masts, mast positions and inclination, and sail shape. During the America’s Teacup the boat had proven to be too gilt-edged. In the following month I designed three new sail plans keeping the same surface area but slightly altering the vertical elongation and adopting a mast with a lower angle towards the stern. The final test, over a weekend, was done just outside Montreal on a cold, snowy day in early December 1970. Hans Fogh, Ian Bruce and I energetically strained the boat under sail, trying various mast and sail solutions until we decided on the one that seemed to yield the most in the wide range of winds and with different weights on board. It was there that we fixed the details of the rigging and nothing has changed since. It was also a nice coincidence with the adoption, that same evening, of the name Laser. During a reception at the Royal St. Lawrence Yacht Club, a young science student approached lan Bruce and said, “You should give the boat a name that is really modern and in keeping with the space age, maybe something scientific.” lan said, “I guess something like Laser would be fine”; and the student replied, “Yes, Laser is just fine!”

Very rapid popularity

Ian called me over the table and said, “How about Laser ?” and I said, “Perfect!” And Laser it was, and it didn’t take long to realize that we had found the perfect name. Laser beam reflects a phenomenon familiar to all young people today, the term is international and gives the impression of something very efficient and up-to-date. From that moment on, the boat gained popularity very quickly. It is hard to say exactly why and I think there are several reasons. It gave the impression that it was the right boat at the right time: it caught the imagination of many good sailors and we soon found that the competition within the class was getting fierce. Not only that but, throughout America, those selling the boat were almost always well-known sailors, some with Olympic medals and international champions. Later the same thing happened in Europe, and many excellent sailors became interested in spreading and taking “the little sailboat” to regattas. Of course by this time we had realized that the Laser was destined to become something much more than a pleasure boat. Ian Bruce and his partner Ward McKimm, two of Canada’s best international helmsmen, “jumped in” to spread the Laser around the world. The second yard was built in California so that boats did not have to be transported from Montreal to the American West Coast. The third yard was established in England to supply boats to the United Kingdom and northern Europe. The Dutch and Swedes were the first Europeans to adopt this class: then it spread to Switzerland under Renaud Langer, a watch designer who now heads distribution in Europe. Langer has a habit of getting things done–on time. Soon, yards sprang up in New Zealand and Australia, countries where there is a tradition for light, fast boats. Next came the problem of supplying the huge southern European market clearinghouse. France, Italy, Switzerland and Germany were all considered suitable countries for a large European shipyard. But at the end of the day, because of taxes and transportation costs, such an enterprise was set up in southern Ireland. Other shipyards would soon be in operation in Brazil and Japan.

“We can’t not have it!”

All of these factories are either owned by Performance Sailcraft or its affiliates: namely, the company that Ian Bruce initially created to build the Laser. “Monopoly” construction was one of the main obstacles to recognition by the International Yacht Racing Union. Many IYRU delegates argued that the organization could not possibly support a single world builder. But others from the various committees-including the president, the Italian Beppe Croce-realized the importance of such an operation. With the presence of a single builder there was no danger that one yard more than the other would set out to make a better boat, what has been the biggest problem for other international classes. With the Laser, the construction technique was moto carefully determined initially and is followed to the letter by every yard. The last thing in the world that Performance Sailcraft wants is a better or worse Laser or a cheaper or more expensive Laser. The primary interest of the builder, as well as that of the buyer everywhere, is that the boat remain exactly the same no matter where it is built. It is worth pointing out that many IYRU delegates took a very thorough look at the organization’s bank account when they considered the Laser class’ application for international status. When that application was submitted in 1972, there were at that time nearly 10,000 boats already in operation. At one dollar per boat the bill was done and it was a nice help to the Union budget. But the decision was delayed for a year, and by that time the Lasers had grown to 17,000. As one of the delegates said in 1973, “We can’t afford not to have this boat.” Further assurance that the Laser was one-design came in 1974 with the adoption in Annapolis, Maryland, of a computerized system for cutting the sails and securing the stitches along the seams by ultrasound so that the shape could not badly be changed. Initially Hans Fogh made all sails in his Toronto sailmaking shop. Because of the huge quantity-up to 40 sails a day-he got excellent assistance from the Dacron manufacturers. There are many weaving looms busy just making fabric, 24 hours a day, for the Laser, in the Boston plant. The sails continue to be cut on exactly the same pattern devised at the time by Hans Rogh, and they are the same ones we chose that wet, windy day in Montreal in 1970. Only now each third is cut with minimal tolerances by a computerized machine. Then the seams are stapled, also with computer-adjusted precision, and the sails are thus distributed to different sailmakers around the world where there are laser factories. The sailmakers do the stitching put the corner reinforcements and the board as well as the grating. But none of this work can change the characteristics of the sail, which are dictated by the electronic computer. The IYRU is very pleased with this system, as this further ensures a uniform product and also escapes the accusation of monopoly by allowing sailmakers in different countries to supply sails and thus have an economic benefit. Of course, I am partisan toward this “little boat that” was born out of an occasional phone call, but when I think of the Laser from the point of view of the journalist, which I was long before I became a boat designer, I can see this class, in perspective in its gradual growth and spread throughout the world. as destined to increase further. Communist countries oppose the spread of the boat on the pretext that and producing it is a monopolistic enterprise, but at the same time many excellent sailors in Eastern Europe are willing to admit that the Laser is indeed a “people’s boat” and is therefore in harmony with Marxist ideology. It is difficult for them to judge favorably a boat that can only be built by one yard: but they like it very much and are persuaded that it would immediately become popular in their countries. All of us, intimately involved in the Laser affair, kept a close eye on the market these first two years, to see if there were any signs of saturation. But then we began to realize that there is really no saturation point. There are always enough new people coming into sailing around the world to cause the steady growth of this class for many years, maybe forever. And the more the Laser expands, the more stimulating it is for me to look back at the original drawings, sketches and calculations and think how many people get joy out of it.

Bruce Kirby

Share:

Are you already a subscriber?

Ultimi annunci

Our social

Sign up for our Newsletter

We give you a gift

Sailing, its stories, all boats, accessories. Sign up now for our free newsletter and receive the best news selected by the Sailing Newspaper editorial staff each week. Plus we give you one month of GdV digitally on PC, Tablet, Smartphone. Enter your email below, agree to the Privacy Policy and click the “sign me up” button. You will receive a code to activate your month of GdV for free!

You may also be interested in.

Michele Molino, nautical engineer with the sea in his vein

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

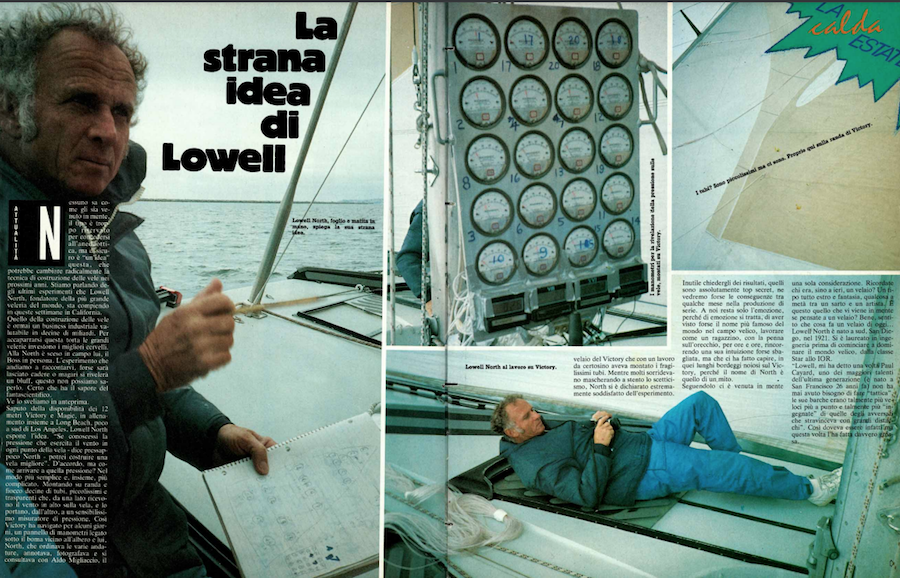

1985. The sails of the future are being born. The GdV is in, with Lowell North

Welcome to the special section “GdV 5th Years.” We are introducing you, day by day, An article from the archives of the Journal of Sailing, starting in 1975. A word of advice, get in the habit of starting your day

Marinedi, the integrated hospitality system

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions

Naval revolution goes through Judel/Vrolijk study

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Sailing, the great excellences of the sailing world tell their stories and reveal their projects. In this column, discover all the companies and people who have made important contributions